Welcome

Home

welcome to the site! Read the description to the left for details regarding the theory behind this site. Some may know this section as an "Abstract"

The History of Energy

the beginning is the end

Under this section is a paper written for an Honours Psychology course, the History of Psychology. The task was to trace a topic from contemperary Psychology back through various historical stages to see how that topic has grown over the course of time. The topic I chose was energy, or Energy Psychology. Enjoy research from Feinstein (most recent) all the way back to Pythagoras.

The Future of Energy

the end is the beginning. This section includes all the previous homepage fails ;) enjoy!

Psychology

This is the major veiwpoint taken on this site in regard to these topics, but since the completion of my Masters degree in Gender Studies, I've been trying to go back and make it more inclusive. This link includes a proposed field theory for Psychology because the two major branches of Psychology (quantitative and qualitative) find it hard to see eye to eye. This (and the next) section is for members only.

Physics/Math

This section proposes a Grand Unified Field theory or "theory of everything" for Physics, backed up by a mathematical equation.

Science/Religion

This section unites all sections together to unite the branches of Science and Religion. Many different perspectives are taken and these two seemingly opposing forces are united through many different angles.

New Age/Orthodox

This section looks at the conflicts or cycles between New Age free thought and Orthodox dogmaticism. The feud between these two opposing forces revealed the truth regarding the story of Jesus, what he really taught and to whom he truly gave the rites to teach his faith. This section explores why the movie The Last Temptation of Christ was banned in other countries, looks at the Da Vinci Code and presents a controversial paper/theory showing the hidden meaning of world religious symbols.

Spirituality

This section begins with a confusing paper about taking back the spirit. If the point can be penetrated, it tells an interesting story about Modernity and the Age of Reason, with a twist by providing evidence that emotion could be considered superior to reason. It also complicates Carteasian mind/body distinctions by adding spirit back into the equation. Have fun following that one lol. I can't even follow it ;) There are other papers about explaining Mystical experiences and others comparing Western and Eastern styles of consciousness. My favourite is the book review of Kabbalah. I like how this site allows me to go back and fix/reword old papers/ideas. This section really details what it is like to have a theory in the making and shows how ideas develop over time. One day my ideas/theory will be comprehensive to others outside my wacky brain :)

Metaphysics

This section includes research done on the importance of emotional charge on ESP communication. It proposes that it is emotion communication that makes telepathy successful. The second paper in this section addresses dreams and dream interpretation. Two Dream interpretation methods (Freud's and Jung's) were analyzed to determine which method produced the most accurate results. The third paper presents research on Understanding Altered States of Conciousness and the last paper in this section is about Western Consciousness and how we are very individualized and perhaps out of balance due to us being lost in the Grand Illusion (Maya). The next paper looks at The Implication of Eastern Concepts on Western Ideals, to propose a potential balance between the two world views.

Philosophy

This section includes a paper about the subject-object dichotomy in Philosophy

Apocalypse

This section begins with a work that is a detailed analysis of the screenplay/poem found in the Art section of this site. This paper looks at the research behind the play that inspired its manifestation (or why I wrote the play). It is hard to avoid the Book of Revelations when the topic of the Apocalypse comes up, so the next paper in this section is a comparison of the similarities and differences of the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelations. Many similarities were found and the research leads one to beleive that we are in the dawning of the Age when we will see great changes in the world as we know it today.

Solutions

This section includes papers on 3 pathways to happiness (physical, mental, emotional), followed by a paper on how to end prejudice, a paper on the polarization of the sexes is next (as it is hypothesized by this site that the true or pure unification of All That is in the Universe is solved by the reunification of the energy of the sexes ;). Finally, this section ends with an empirical thesis exploring the equal validation or rational and emotional styles.

Art/Screenplay

This section contains a play or screenplay called the Grand Drama that is written entirely out of prose (the owner and creator of this website has personally written everything that appears on it). This work of art reveals a hidden message, one that may unlock the key to the mysteries of the universe! This page also includes a shortened poem of the Grand Drama and provides a link to a song that is about Plato's Analogy of the Cave (members only).

Poetry

this is a collection of my poetry - enjoy!

Songs

This is a collection of my songs - enjoy! =)

Photos

This is my photo collection

Key to the Legend

Red = Philosophy

Blue = Physics

Yellow = mathematics

green = hard sciences

grey = psychology

the parts under construction are labeled as such or blanketed by <<< ____ >>> indicating personal notes to self to improve the site, or the layout of the information presented.

Recent Videos

Interdisciplinarity and Women's Studies

December 14, 2011

The Advancement of Women’s Studies: Following the PhD Debate

There is controversy over the prospect of creating PhD programs in women’s studies. When confronted with creating doctorial programs in women’s studies, there are scholars that oppose the idea (Friedman 301; Brown 36) and those that believe it is an important step in which the future of women’s studies may depend (Allen and Kitch 292). Problems with creating doctoral programs in women’s studies include whether or not to define women’s studies as a discipline demanding its own departmental status, or to be defined as an interdisciplinary field (Boxer 387). Defining women’s studies within either of these definitions is important in determining whether or not “course work [should] be housed exclusively in traditional departments or in a separate administrative unit” (Boxer 387). Brown poses the same question when she asks if feminist courses should be conducted in “the context of a degree-granting program” or whether it should be ‘mainstreamed’ into “traditional curriculums” (Brown 35).

Moving away from the curricula residing exclusively in a freestanding department or within traditional disciplines, other scholars such as Pryse and Lykke, believe women’s studies doctoral curricula could reside in both a freestanding program and within traditional disciplines simultaneously. But in order for this fluctuation to occur, women’s studies need to be considered a freestanding discipline. This is where much of the debate lies because the boundaries of women’s studies, the core content it should teach and what core methodologies women’s studies can claim remain in dispute.

In regard to defining women’s studies as either a discipline or interdisciplinary, this is also a matter of dispute. There is an underlying assumption that women’s studies are interdisciplinary, yet much of the work lacks true integration of epistemology and methodologies across disciplines and thus cannot be considered truly interdisciplinary (Allen and Kitch 275). Therefore, arguments have been made that the work and research conducted in women’s studies is actually more multidisciplinary than interdisciplinary because there is more collaboration than integration (282).

Other scholars define women’s studies as transdisciplinary as it goes “beyond or above” disciplinary boundaries (Pryse 105) and epistemology and methodology “are articulated in ways that are not ‘owned’ by any specific disciplines” (Lykke 142). Lykke takes the definition of women’s studies to a whole new level by defining it as an emergent, postdisciplinary field, which not only goes beyond disciplinary boundaries, but becomes “modes of organising academic knowledge production [that ends up with the] removal of the traditional disciplinary structures” (Lykke 143).

Inserting women’s studies into one or any of these definitions is important for determining whether or not women’s studies should create PhD programs because if PhD programs should be created, Marilyn Boxer believes the decision of where doctoral curricula should reside depends on one’s definition of interdisciplinarity (390/391). “Depending on [professor’s] perspectives about discipline-based education and their definition of interdisciplinarity, they may envision a freestanding program or one that involves collaboration among departments” (Boxer 390/391). If women’s studies are defined as a discipline in itself, then the curricula can exist within a ‘freestanding program’ (ibid). Considering it as multidisciplinary or interdisciplinary, then the curricula may reside in traditional departments. If women’s studies is defined as transdisciplinary or postdisciplinary this implies women’s studies curricula may reside in a combination of the two, creating new epistemologies and methodologies and even becoming a new emergent entity that could radically reconfigure academia. This paper will follow the debates regarding the PhD program in women’s studies by exploring the various definitions assigned and will determine whether the curricula should reside in a ‘freestanding discipline,’ within traditional disciplines or a combination of the two. Suggestions of what the core curricula would be and how a fluctuation between freestanding and traditional disciplines would be possible will also be discussed.

WOMEN’S STUDIES AS A DISCIPLINE

If women’s studies are to create PhD programs, there is much concern over what core knowledge and what core methodologies should be taught (Brown 19; Friedman 313). Therefore, in order to be considered a stand-alone discipline, women’s studies needs to have core content and core methodologies to claim as their own. If this could be determined, then the curricula can reside within a freestanding discipline. My working definition of a discipline would be one in which has core epistemology and methodology. I will not be using Friedman’s definition “confining knowledge within certain sets of limiting boundaries” (Friedman 309) because women’s studies could never be defined in this way.

When asking what epistemology would be at the core of women’s studies, Brown mentions that by placing “The political” at the core of women’s studies is problematic (Brown 18), but believes placing gender at the core of women’s studies to be even more problematic (34). Gender at the core would define women’s studies as a Second Wave feminist pursuit that, in the end, is excusatory of women of colour; thus some professors would be hesitant or even opposed to teaching gender focused material (Brown 34). Gender cannot be considered the core concept of women’s studies because “the expansion of women’s studies [has moved] far beyond the boundaries of gender alone” by incorporating systems of intersectionality (Friedman 316).

Narrowing women’s studies down to one core concept creates a paradox because this would be like saying the human experience or identity can be narrowed down to only one aspect, such as gender (Brown 24). Brown states that powers “do not operate on and through us independently, or linearly, or cumulatively…[much like how intersectional] powers of subject formation are not separable in the subject itself” (24). Therefore, like how our identity formation is influenced by intersectionality, women’s studies are also influenced by interdisciplinarity, making finding one core concept extremely problematic.

In regard to finding core content in women’s studies, Brown asks the question “[i]s it possible to radically reconfigure women’s studies programs without sacrificing the feminism they promulgate…(35)? This is an important question because those who do not know what women’s studies teach generally assume gender and feminism to be at its core and if gender and feminism are not at the core, then what is? I would like to suggest a potential core for women’s studies as they revolve mostly around systems of oppression and power dynamics. Oppression and power, in my opinion, encompasses and better represents the true core of women’s studies. If this was accepted as the core concept, women’s studies may then be defined as a discipline and the curricula could reside within “a separate administrative unit” (Boxer 387). But, to accept power and oppression as the core, would it necessitate a name change from women’s studies to something else? Would departmentalizing ‘radically reconfigure’ women’s studies as we know it? Responding to this, Allen and Kitch make the point that “other fields, such as African American studies, religious studies, and criminal justice, departmentalized years ago without losing their identities…” (291).

To define women’s studies as a separate discipline, it demands that not only the core content or epistemology be considered, but also the methodology. There is much concern over what methodologies should be taught as core to women’s studies if a PhD program were to be created (Boxer 387; Friedman, 313; Brown 19). To suggest that women’s studies is a discipline in itself, is to imply that there is “something called method…that unifie[s] all feminist research and thinking” (Brown 19). The idea that there can be a core methodology is disputed because there are so many different ways in which to conduct research in women’s studies.

Women’s studies has embraced many non-traditional methodologies such as comparative research, which can be found in Munoz’s Cruising Utopia, Standpoint Theory that stresses the importance of intersectionality, context and background in research, Experiential aspects, using autobiographies as case studies, using poetry to piece together autobiographies, using art as activism, ethnography, interviews, surveys and using films and books as relevant research material. This is by no means an exhaustive list, and as varied as these methodologies seem, there is a common thread. They are all methods of qualitative research. I might even argue that the suggested core epistemology for women’s studies (oppression and power dynamics) remains consistent throughout these methodological approaches because when these methods are applied, concepts such as reflexivity, and ‘who has the power’ are taken into consideration with academic rigour.

It could be argued that in order to be a stand-alone discipline, said discipline need not pick only one particular method to be at its core, but perhaps one family of research methodologies, such as qualitative research. I am not saying women’s studies do not utilize quantitative methods, but I would not place quantitative methods at the core of women’s studies as a defining characteristic. Much like how psychology utilizes both quantitative and qualitative methods, I would not place qualitative methods at the core of psychology.

In conclusion, in order to consider women’s studies as a discipline, there needs to be core knowledge and core methodology uniting it as a cohesive whole. I propose that women’s studies could be considered a stand-alone discipline if the core content or epistemology was considered to be systems of oppression and power dynamics, and the core methodology qualitative measures. However, just because women’s studies could be considered a discipline in itself, does not mean its doctoral programs should reside exclusively within a ‘freestanding discipline.’

WOMEN’S STUDIES AS MULTIDISCIPLINARY

Many scholars maintain that making women’s studies a disciplined department with a contained PhD program is impossible (Friedman 301; Brown 36). Since women’s studies are so broad, and since PhD programs demand specialization, it would necessitate the collaboration with other disciplines. Students coming into graduate women’s studies programs are from many different backgrounds and Brown asks us to “consider how difficult it is to teach contemporary feminist theory to students who share none of the intellectual referents of the feminist theorists they are reading” (35). It might be suggested that upon entering graduate programs, students could be given a crash course in women’s studies basics. But, this too is problematic because a student, who has already acquired an undergraduate degree in women’s studies, would not be learning beyond their undergraduate work, as graduate work demands (Friedman 317). The fact that this problem exists, suggests women’s studies is to be defined as multidisciplinary, rather than a discipline and the curricula should perhaps be ‘mainstreamed’ into traditional disciplines.

Multidisciplinarity is defined here as “a collaboration between different disciplines around a shared research problem that maintains a strict division of labour between the disciplinary cannons and modes of working” (Lykke 142). For example, researcher from women’s studies, working with researchers in psychology can work together on a topic, but it would be likely that the women’s studies academic would approach the topic in a qualitative and reflexive manner and the psychology academic would most likely approach the topic using quantitative methods. This definition does seem to be an accurate description of research in women’s studies. Allen and Kitch believe women’s studies to be more multidisciplinary than interdisciplinary because work and research in women’s studies is more collaborative than integrative (277). Boxer also agrees that the term multidisciplinary is a “more accurate” definition for women’s studies (Boxer 389). Defining women’s studies as multidisciplinary may suggest that its doctorial curricula should reside outside a ‘freestanding discipline’ and be integrated into traditional disciplines.

Going back to the concern surrounding finding a core methodology, Friedman states that the potential methodologies conducted in women’s studies are so varied, that “they hardly share a common methodological language and can barely understand each other’s research” (315). This could support the idea that women’s studies are more collaborative than integrative. Although, Friedman used this as an argument against creating a freestanding doctoral program, this also poses a problem in collaborating with other departments while maintaining strict modes of thinking about and conducting research. According to my personal observation and research, all disciplines do study similar phenomena and topics, making collaboration a possible option, but they do seem to bring in their own language and terms when describing said phenomena. Therefore, I agree there may be a potential language barrier when in comes to multidisciplinarity.

There may be a potential solution for this language barrier and I propose a General Systems Theory “Part 2.” In 1968, Ludwig von Bertalanffy noticed that all the branches of science had similar theories, but were using different language. “Not only are general aspects and viewpoints alike in different sciences; frequently we find formally identical or isomorphic laws in different fields” (General Systems Theory). He desired to integrate the sciences, both natural and social and believed collaboration was needed for furthering all education (General Systems Theory). He developed a theory in which all branches of science could agree, while using their similar theories. I propose this idea could be applied to the disciplines within women’s studies, and be utilized especially between those collaborating on research. Perhaps interested representatives from each department collaborating on a topic or research could meet and discuss their similar concepts. This could aid in communication across various disciplines because when a concept is explained in layman’s terms, without using specialized jargon, you would be surprised how many disciplines would recognize that concept as a part of their own studies.

The prospect for curricula in doctorial women’s studies is promising if a multidisciplinary approach were to be implemented. Perhaps specialized jargon or ‘psychobabble’ should be kept to a minimum or defined really well when researching topics that could be utilized across disciplines. However, just because multidisciplinary work lends itself nicely to women’s studies research, it does not mean the potential doctoral curricula should remain exclusively within the traditional disciplines.

WOMEN’S STUDIES AS INTERDISCIPLINARY

Interdisciplinarity implies integration whereas multidisciplinarity implies disciplines work along side one another, while maintaining their boundaries. Lykke’s definition of interdisciplinarity allows “boundary work and boundary transgressions to take place between different disciplinary modes of working” (142). This means that the disciplines involved would understand and utilize each other’s epistemology and methodology and not keep strict boundaries. Upon reading this definition, it does seem women’s studies are more suited for multidisciplinary rather than interdisciplinary work. Friedman is highly sceptical of integration as she believes “methodological divides across the divisions are enormous, particularly between quantitative and qualitative approaches” (315).

This could be why it is suggested that students should get their degrees in traditional disciplines instead of women’s studies because degrees in women’s studies could “impoverish their education” (Brown 19). Friedman states that “interdisciplinarity is most successful when it emerges out of a firm grasp of the knowledge bases and methodologies of at least one of the existing disciplines” (312) and that it is “very difficult for people with interdisciplinary PhD’s in women’s studies to succeed on the academic market” (305).

This poses a problem in making PhD programs in women’s studies; the lack of jobs because “most hiring follows traditional categories for specialization” and women’s studies is too interdisciplinary to be considered a department (Friedman 304). In response to this, Allen and Kitch would disagree and say that creating PhD programs is essential to the furthering of the field and in turn creating jobs for those with interdisciplinary degrees (292). “[W]ithout departments into which interdisciplinary scholars can be hired, there will remain scant justification for interdisciplinary women’s studies PhD programs” (Allen and Kitch 292). I agree with this statement because the more women’s studies departments, the more jobs for those with interdisciplinary degrees. However, unfortunately, I also agree with Allen and Kitch’s concern regarding the field’s growth when they suggest that its growth is stunted because the “university has failed to take [women’s studies] seriously” (289). This could explain the lack of academic placements, more than the lack of interdisciplinary appointments.

I would like to pose a way in which women’s studies may gain more credibility within the university so it can be taken more seriously, by proposing a way to make women’s studies truly interdisciplinary. Perhaps if the vast amount of qualitative research conducted in women’s studies were to be standardized, it may help further the growth of the field. By standardization I mean that each researcher uses the same survey and/or interview questions. Each researcher could add their own personalized questions as long as some are standardized. Standardization allows parallels and comparisons to be made across research projects.

To initiate this idea, I suggest something similar to what psychology has done with questionnaires. A researcher develops a questionnaire (which can be compared to survey or interview questions), then tests the reliability of the measure mostly by publishing the questionnaire along with the article for other researchers to use. The more researchers using the questionnaire, the more the data can be pooled and compared. It happens often that researchers find flaws in the questions and improve upon the questionnaire, in which the next researcher takes and improves. The researcher could either replicate the study/experiment or use the same questionnaire for a completely different hypothesis.

I propose this method could be applied to surveys and interview questions in women’s studies. By publishing the questions (and even the transcripts of the answers) with the article, other scholars can replicate the research and/or find different interpretations of the transcripts to add to the overall knowledge of the topic. If the survey and interview questions are standardized, the information can be used to draw comparisons, contributing to the pool of knowledge on that topic, and thus gaining respect from the university. The larger the qualitative database, the better.

Once a database has been created, the research would not just help epistemology within women’s studies, but also contribute to other disciplines. For example, psychology could benefit from important missing qualitative information provided by women’s studies research. Research conducted in a laboratory setting produces results that are not representative. Ethnographic research from women’s studies makes up for the flaws in quantitative strategies. Integrating the qualitative research with the quantitative research on the same topic produces a more complete picture.

To have this work the other way around, and add quantitative research to qualitative is a little harder due to the language. To get around this issue, most quantitative research is written in APA format which breaks the paper into sections and the confusing information usually resides within the Methods and Results sections. When papers are formatted in this way, it allows the reader to skip these sections without missing out on relevant content. Another useful integration technique would be for those who use quantitative measures to use reflexivity when conducting their research and for those who use qualitative measures to adapt Harding’s ‘strong objectivity’ by “explor[ing] gaps in the research questions and representational techniques the traditional disciplines have adopted…” (Pryse 115).

Creating a qualitative database with standardized survey and interview questions, integrating each other’s research techniques, and if more attempts were made by both psychology and women’s studies to read each other’s research, this could integrate the two fields, producing true interdisciplinarity and closing the gap between quantitative and qualitative measures. Adding courses from departments like psychology would also allow for bolder course offerings and show the university that women’s studies can cover “more than marginal course content” (Pryse 113). By doing all this, it would therefore, demonstrate to the university how important qualitative research is and would see women’s studies as an asset to academia. Universities may then begin to take women’s studies more seriously, providing women’s studies with the credibility and recognition it has always deserved. This new interdisciplinarity would allow doctoral curricula in women’s studies to reside in both an established discipline and within traditional disciplines.

WOMEN’S STUDIES AS TRANSDISCIPLINARY

In regard to doctoral curricula in women’s studies fluctuating between a home base and traditional disciplines, Pryse believes “[the] challenge…graduate education raises for Women’s Studies concerns precisely the interrelation between disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity” (106). Friedman believes that when curricula are set up in this manner, it creates a too much, too little paradox because “[d]isciplinarity resides in potential overspecialization [and] the danger of interdisciplinarity rests in potential superficiality…[or] rootlessness” (312). I believe creating PhD programs would allow the best of both worlds because it could create a root or home base for students, while they go out into their cross-listed traditional courses as not to be overspecialized. To maintain the home base, the program could hire its own professors who are trained in women’s studies, thus also creating jobs for those who have interdisciplinary degrees.

Pryse develops a way to interact between both disciplinarity and interdisciplinarity by suggesting a “transversal politics” (109). She utilizes Yuval-Davis’ idea of “rooting” and “shifting” or the idea of “’shift’ and ‘pivot’ as an ongoing aspect of …methodological practice…while remaining grounded” (Pryse 110). By ‘rooting’ she suggests that “students as well as faculty [need] to ‘root’ themselves in a particular set of methods borrowed from or learned within the traditional disciplines” (Pryse 110). Even though I have a strong background rooted in quantitative psychology, I find that a strong background in qualitative methods utilized in women’s studies to be just as appropriate for this root and thus this ‘root’ does not necessarily have to be ‘borrowed from a traditional discipline’ because qualitative measures are just as valid as any other measure.

While interdisciplinarity implies integration and transgression of boundaries across disciplines, transdisciplinarity implies that the interaction can create new boundaries and methodologies that are not “‘owned’ by any specific discipline” (Lykke 142). Marjorie Pryse also utilizes the prefix “trans” to “offer new ways to think about interdisciplinarity in Women’s Studies” (105). Therefore, in my understanding, the ‘root’ is only temporary as it would be integrated with other ‘roots’ to create new and different methodologies. Lykke also defines transdisciplinarity as “an example of the development of new thinking technologies that takes place in a space beyond the existing disciplines” 142/143). Yet, neither Pryse nor Lykke provide an example of what this kind of ‘new thinking technology’ would look like.

Using the interdisciplinary idea above, which suggested a way to integrate quantitative and qualitative methods, I would like to suggest a potential example of this new “trans” collaboration and propose new technology or methodology. For example, in psychology, quantitative data is entered into a program called “SPSS” that performs various mathematical formulae, depending what test is suitable for the research topic. In women’s studies, surveys and interview data can be entered into a program called “Atlis.ti.” “This program allows researchers to manage large qualitative data sets through the coding of text and analytic memo writing” (Frisby et al. 20). In the spirit of transcending disciplinary boundaries to create new ‘thinking technologies,’ why not create a computer program that looks for patterns within both quantitative and qualitative data simultaneously? This may be a good example of a ‘new thinking technology’ that “no existing discipline can claim to ‘own’” (Lykke 143). Using this new technology would make women’s studies truly transdisciplinary and the doctoral curricula could fluctuate between disciplinarity and transdisciplinarity by ‘rooting’ and ‘shifting.’

WOMEN’S STUDIES AS POSTDISCIPLINARY

Lykke poses an interesting definition of women’s studies as a postdiscipline. She defines postdisciplinarity as “modes of organising academic knowledge production [that leads to] a removal of the traditional disciplinary structures” and argues for a “mode of organising that takes into account the needs for both transversal openness and stable sites for transdisciplinary reflections” (Lykke 143, emphasis in original). In regard to ‘rooting’ and ‘shifting,’ reflexive work in women’s studies could root in the stable sites and shift for transdisciplinary reflections.

When fluctuating between two variables in a dichotomy, finding a balance between extremes is important, especially when conducting research. Just like how one does not wish to be completely rootless, nor completely overspecialized, Lykke points out that when conducting research one needs to find a balance between objectivity and relativity (146). By defining women’s studies as postdisciplinary she says this conundrum can be avoided (146). To keep a balance and avoid the extremes between objectivity and relativity, she brings in the example of Niels Bohr and how light can exist as both a particle and a wave to show how, depending on the research methodology used, it could be viewed objectively (as a particle) or contextually (as a wave) (146).

Using quantum physics as an example of how to fluctuate or balance the two extremes of objectivity and relativism is helpful because according to relativity, the person looking at the stars becomes the focus or centre for that particular research or point of view. Someone at the other side of the world may have a different point of view of the stars, but it could be argued that locally, the view of the stars is somewhat similar and could be taken somewhat objectively in that local setting (146). This is also relevant for fluctuating between “both transversal openness and stable sites for transdisciplinary reflections” (Lykke 143, emphasis in original).

Rooting and shifting and particle-wave modes of organizing information may fall short when it comes to uniting or transcending the boundaries of many disciplines. To me, rooting and shifting and the prefix ‘trans’ implies interaction or dialogue between two points in a dichotomy, implying only two disciplines are involved. Postdisciplinarity, to me suggests going beyond two disciplines, to encompass all disciplines in the university, or at least to those that could be involved in the topic at hand. In order to encompass more than two disciplines, it may require a mode of organizing information that allows the rooting and shifting through all disciplines. Lykke asks how it is possible to “defy the stabilising foundationalism of canons, evade clear categorical distinctions, and retain space for a free and passionate flow of thoughts” (146).

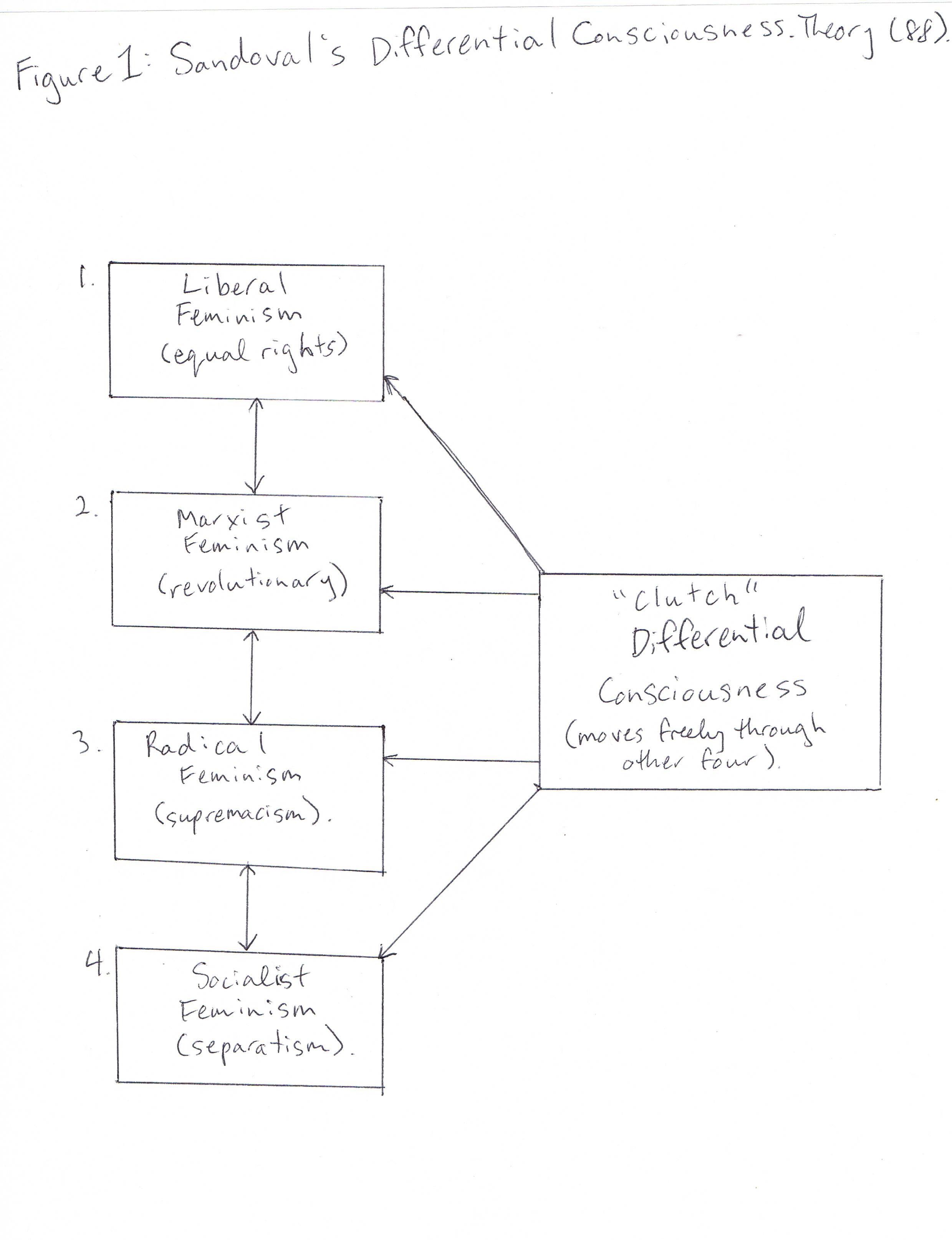

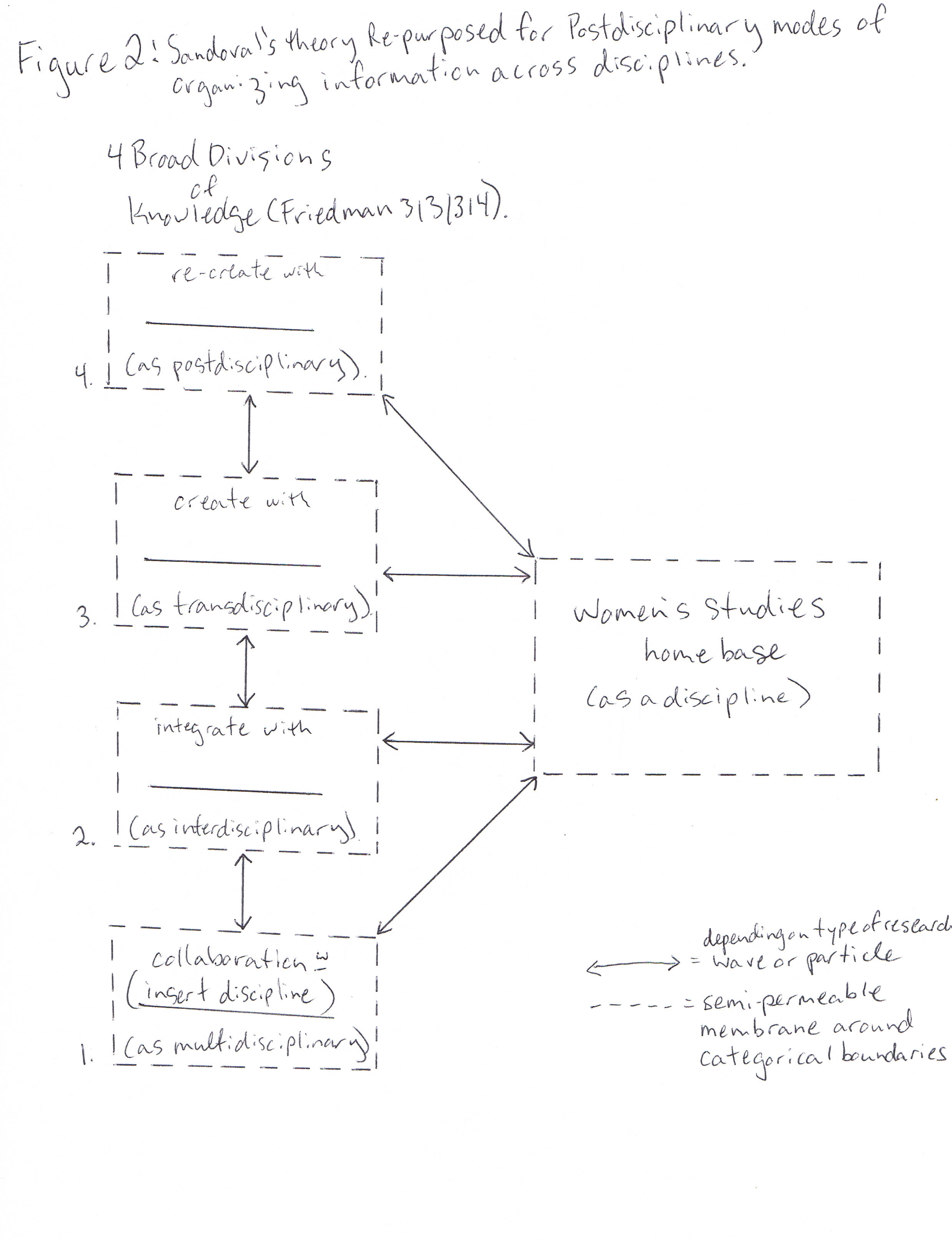

To answer this question, I propose a twist on Sandoval’s theory that could be utilized to shift between different disciplines while remaining stabilized and free. Sandoval poses a theory to unify all feminist theories by setting up four oppositional, mutually exclusive categories that represent different types of feminism and suggests a fifth category that can weave “’between and among’ oppositional ideologies” (87/88). She calls this fifth category a “differential mode of consciousness [that] operates like the clutch of an automobile: the mechanism that permits the driver to select, engage and disengage gears” (Sandoval 88). See fig. 1 for Sandoval’s theory. To repurpose this theory for postdisciplinary work, I would insert different university disciplines into the four categories, replacing the different types of feminism. I would also make the categorical boundaries less ridged by drawing semi-permeable membranes to allow the ‘clutch’ to weave more freely through each discipline (see fig. 2). The fifth differential would be the “space for a free and passionate flow of thoughts” and the clutch mechanism would allow the evasion of “clear categorical distinctions” (Lykke 146) as it moves through the other disciplines. Therefore, suggesting a way to think both freely in interdisciplinarity, while maintaining a disciplined root.

If women’s studies were to be truly postdisciplinary however, this would imply that its new technologies would tear down the strict boundaries of other traditional disciplines, radically reconfiguring academia. Perhaps if the new technology discussed above (of combining SPSS and Atlis ti. programs) were to be created, it would get the attention of other disciplines such as mathematics and computer science. After all, who else would be qualified to create such a program! Therefore, if this technology were to be created, women’s studies may have the potential to radically reconfigure the face of academia and become truly postdisciplinary.

CONCLUSION

Overall, I believe women’s studies to be a discipline deserving its own department. This is important because if “women’s studies isn’t a department and it isn’t a discipline, then it isn’t a research entity (Allen and Kitch 291). But, I disagree that doctoral curricula should reside exclusively with in this freestanding department. I agree with Pryse that there is a way to be both a discipline and an interdisciplinary field and allow the curricula to fluctuate between a freestanding department and within traditional disciplines. This can be possible through particle-wave theory and by utilizing Sandoval’s clutch idea to shift between rooted disciplinary work and interdisciplinary work. But in order to root and shift, a root is needed, so I believe that women’s studies should continue to grow by creating more graduate and doctoral programs. Right now, women’s studies may be most aptly defined as multidisciplinary, but if women’s studies were to advance along the various definitions highlighted in this paper, then not only would it grow as a discipline and gain the credibility it deserves within the university, but could also radically reconfigure academia as we know it.

Works Cited

Allen, Judith A. & Sally L. Kitch.”Disciplined by Disciplines? The Need for an Interdisciplinary

Research Mission in Women’s Studies.” Feminist Studies 24.2 (Summer 1998): 275-300.

Boxer, Marilyn. “Remapping the University: The Promise of the Women’s Studies PH.D.”

Feminist Studies. 24. 2 (1998): 389-405.

Brown, Wendy. “The Impossibility of Women’s Studies.” Women’s Studies on the Edge. Ed.

Joan Wallach Scott. Durham NC: Duke University Press. 17-38. (2008) Print.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. “(Inter)disciplinarity and the Question of the Women’s Studies

PH.D.” Feminist Studies 24.2 (Summer 1998): 301-326).

Frisby, Wendy., et al. “Taking Action.” Mobilizing Communities to Provide Recreation for Women

on Low Incomes. Vancouver: BC Centre of Excellence for Women’s Health, 2001

Lykke, Nina. “This Discipline Which Is Not One: Feminist Studies as a Postdiscipline.” Theories

and Methodologies in Postgraduate Feminist Research: Researching Differently. Ed. Rosemarie Buikema, Gabriele Griffin and Nina Lykke, New York: Routledge. 137-150. (2011). Print.

Pryse, Marjorie. “Trans/Feminist Methodology: Bridges to Interdisciplinary Thinking.” Feminist

Formations. 12. 2. (2000): 105-118.

Sandoval, Chela. “US Third-World Feminism: The Theory and Method of Oppositional

Consciousness in the Postmodern World.” Post Colonial Feminism: A Reader. Eds.

Reina Lewis and Sara Mills. New York: Routledge, 2003. 135-160. Print.

von Bertalanffy, Ludwig. “General System’s Theory.” A Gateway to Selected Documents and Web

Sites (1968). Web. Dec. 13, 2011.