Welcome

Home

welcome to the site! Read the description to the left for details regarding the theory behind this site. Some may know this section as an "Abstract"

The History of Energy

the beginning is the end

Under this section is a paper written for an Honours Psychology course, the History of Psychology. The task was to trace a topic from contemperary Psychology back through various historical stages to see how that topic has grown over the course of time. The topic I chose was energy, or Energy Psychology. Enjoy research from Feinstein (most recent) all the way back to Pythagoras.

The Future of Energy

the end is the beginning. This section includes all the previous homepage fails ;) enjoy!

Psychology

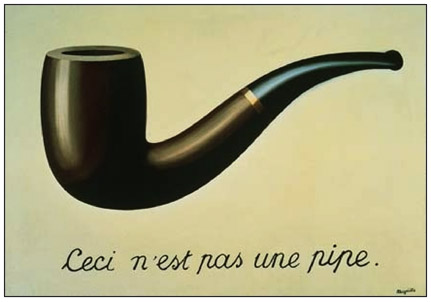

This is the major veiwpoint taken on this site in regard to these topics, but since the completion of my Masters degree in Gender Studies, I've been trying to go back and make it more inclusive. This link includes a proposed field theory for Psychology because the two major branches of Psychology (quantitative and qualitative) find it hard to see eye to eye. This (and the next) section is for members only.

Physics/Math

This section proposes a Grand Unified Field theory or "theory of everything" for Physics, backed up by a mathematical equation.

Science/Religion

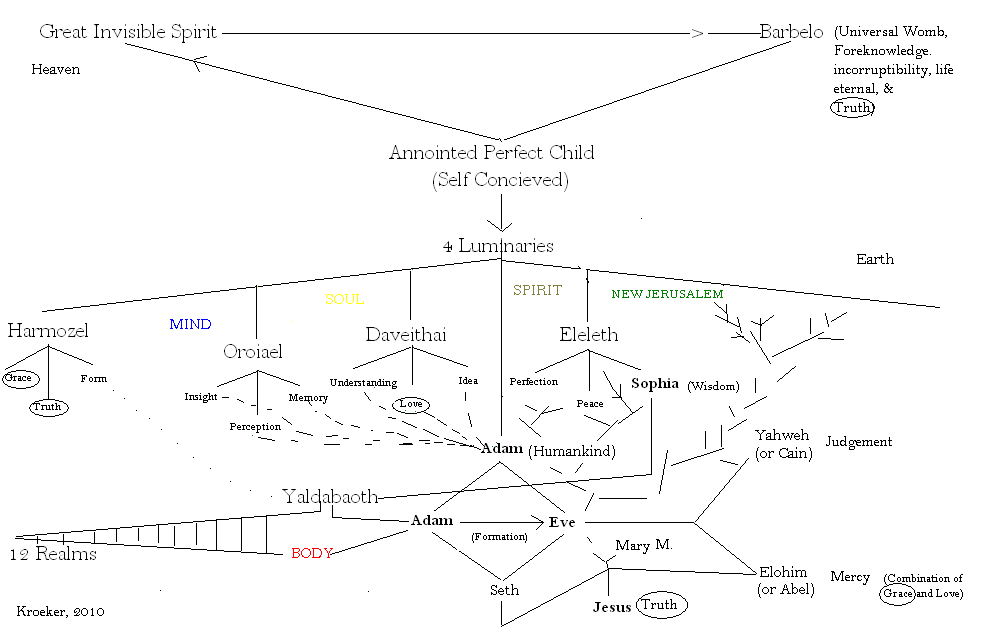

This section unites all sections together to unite the branches of Science and Religion. Many different perspectives are taken and these two seemingly opposing forces are united through many different angles.

New Age/Orthodox

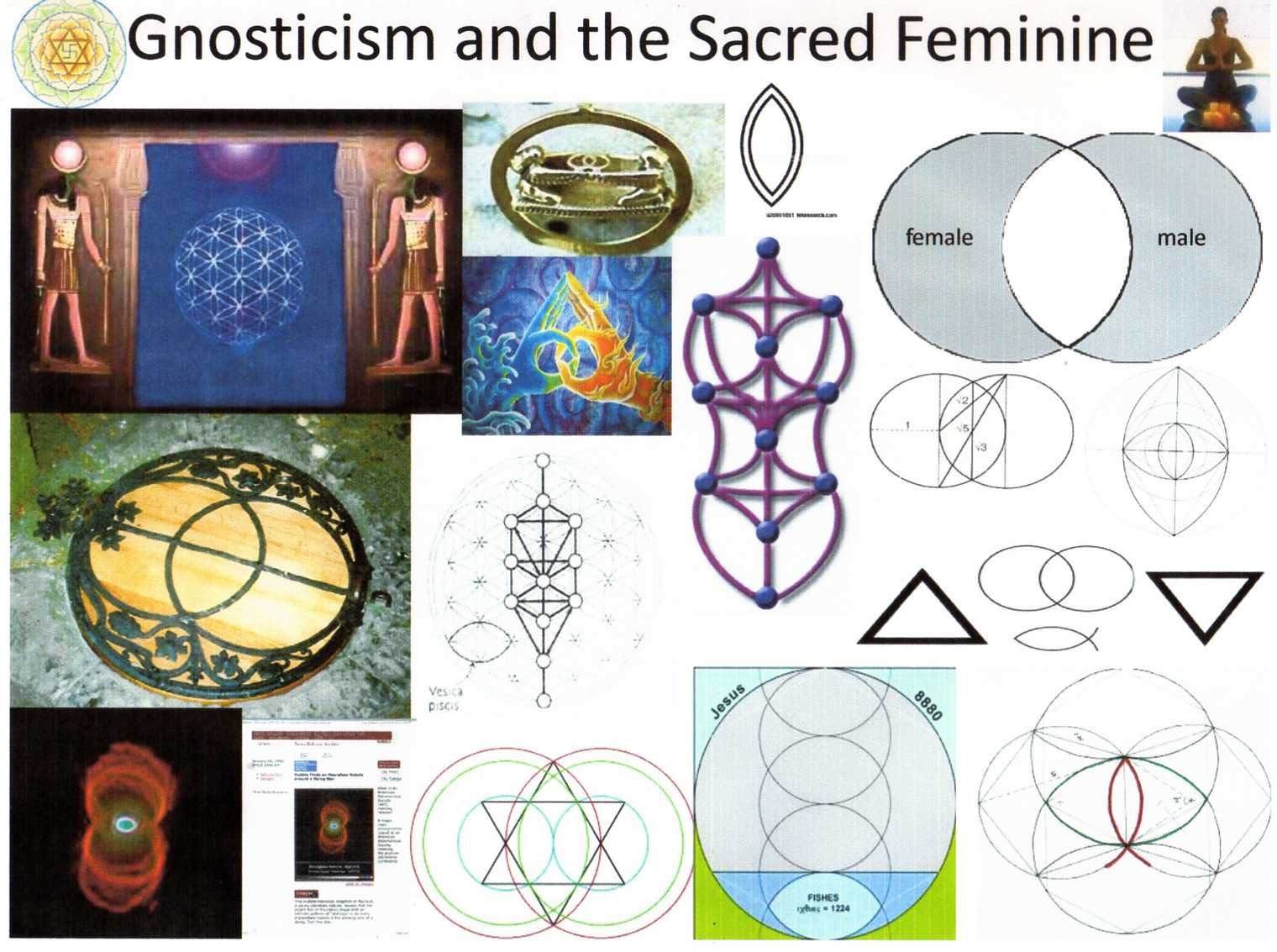

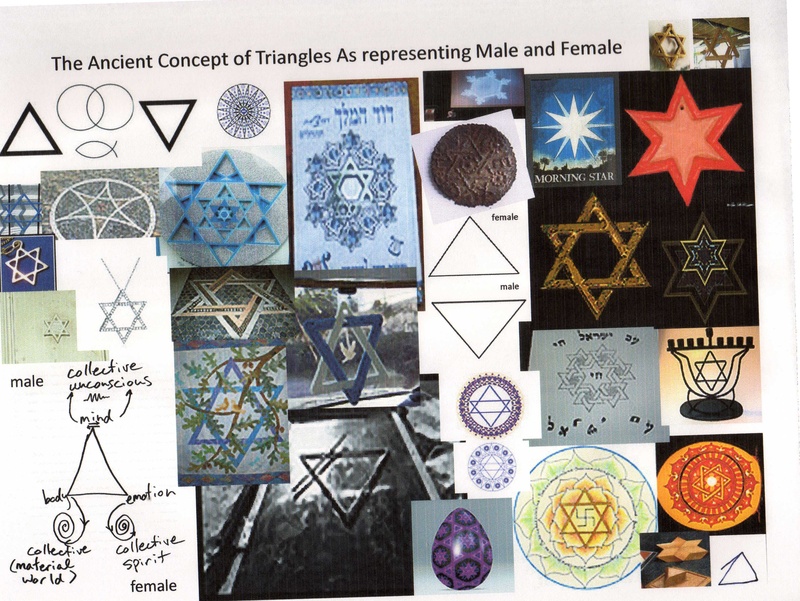

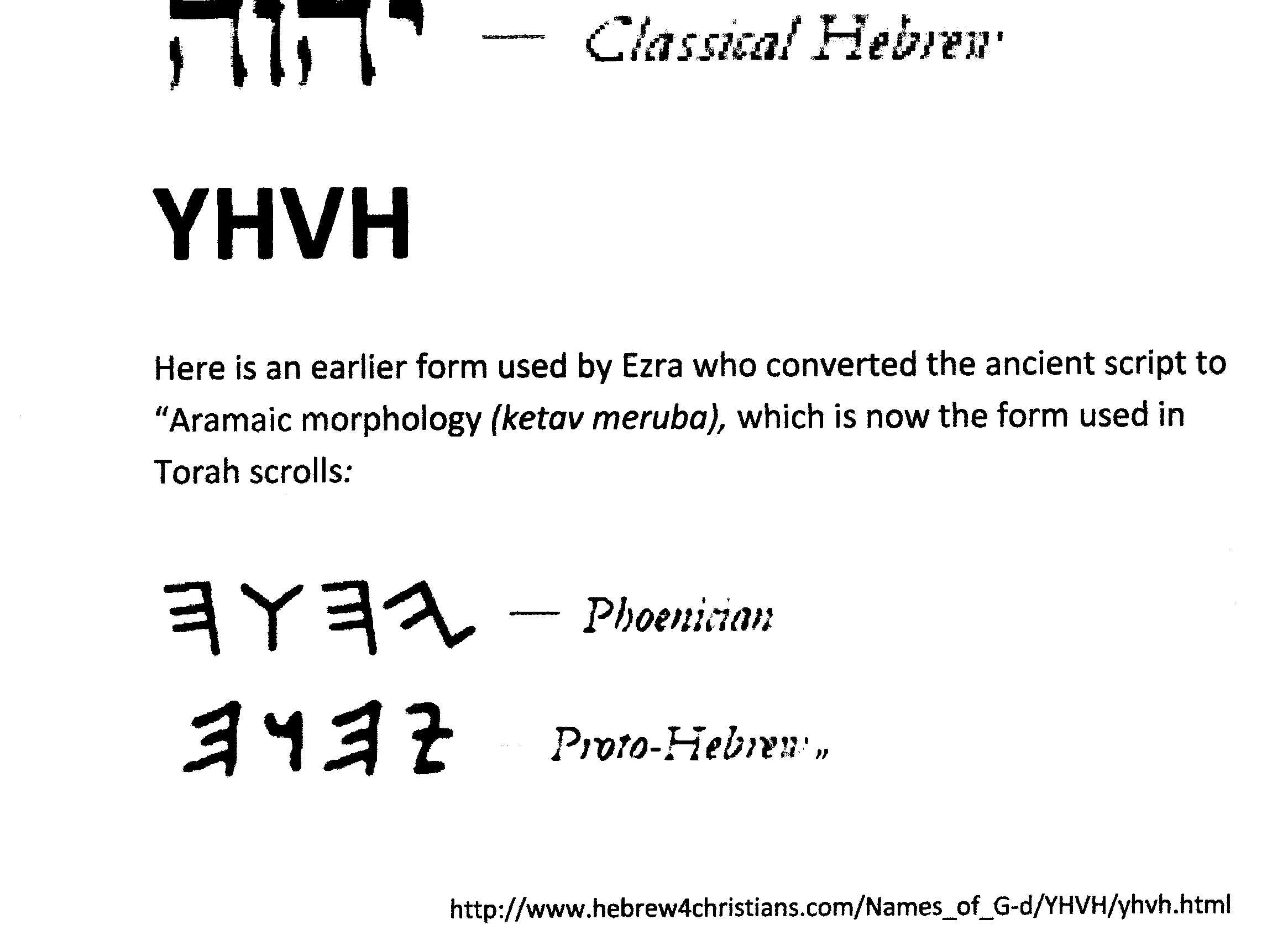

This section looks at the conflicts or cycles between New Age free thought and Orthodox dogmaticism. The feud between these two opposing forces revealed the truth regarding the story of Jesus, what he really taught and to whom he truly gave the rites to teach his faith. This section explores why the movie The Last Temptation of Christ was banned in other countries, looks at the Da Vinci Code and presents a controversial paper/theory showing the hidden meaning of world religious symbols.

Spirituality

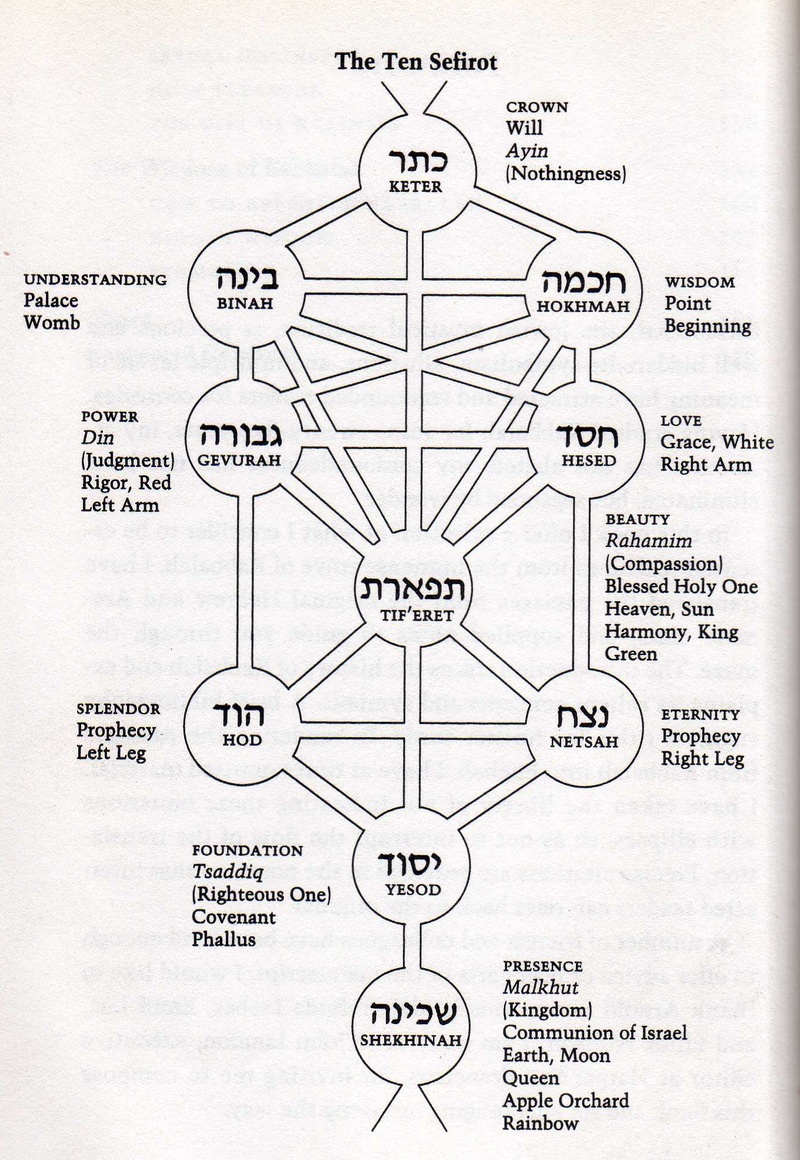

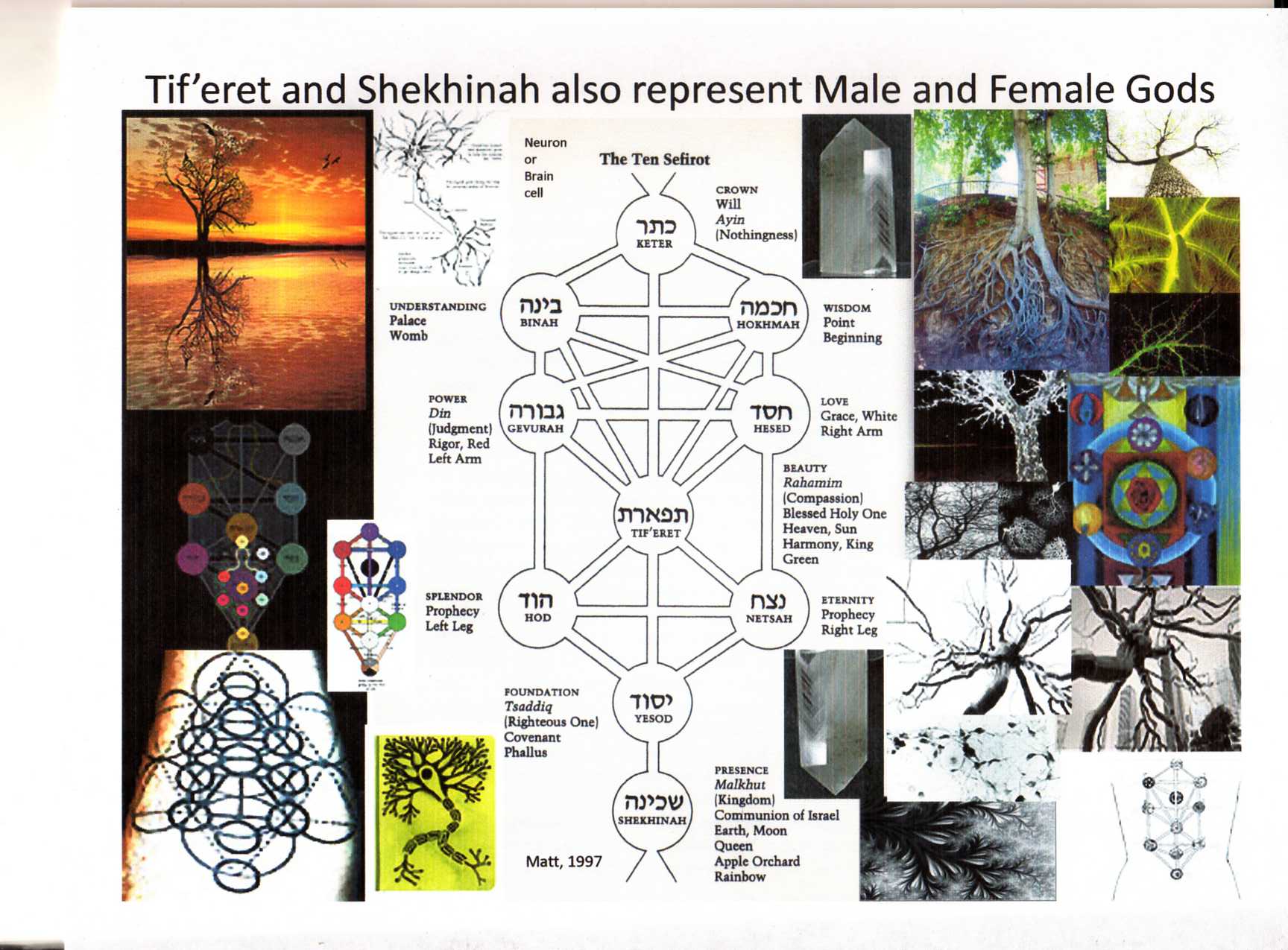

This section begins with a confusing paper about taking back the spirit. If the point can be penetrated, it tells an interesting story about Modernity and the Age of Reason, with a twist by providing evidence that emotion could be considered superior to reason. It also complicates Carteasian mind/body distinctions by adding spirit back into the equation. Have fun following that one lol. I can't even follow it ;) There are other papers about explaining Mystical experiences and others comparing Western and Eastern styles of consciousness. My favourite is the book review of Kabbalah. I like how this site allows me to go back and fix/reword old papers/ideas. This section really details what it is like to have a theory in the making and shows how ideas develop over time. One day my ideas/theory will be comprehensive to others outside my wacky brain :)

Metaphysics

This section includes research done on the importance of emotional charge on ESP communication. It proposes that it is emotion communication that makes telepathy successful. The second paper in this section addresses dreams and dream interpretation. Two Dream interpretation methods (Freud's and Jung's) were analyzed to determine which method produced the most accurate results. The third paper presents research on Understanding Altered States of Conciousness and the last paper in this section is about Western Consciousness and how we are very individualized and perhaps out of balance due to us being lost in the Grand Illusion (Maya). The next paper looks at The Implication of Eastern Concepts on Western Ideals, to propose a potential balance between the two world views.

Philosophy

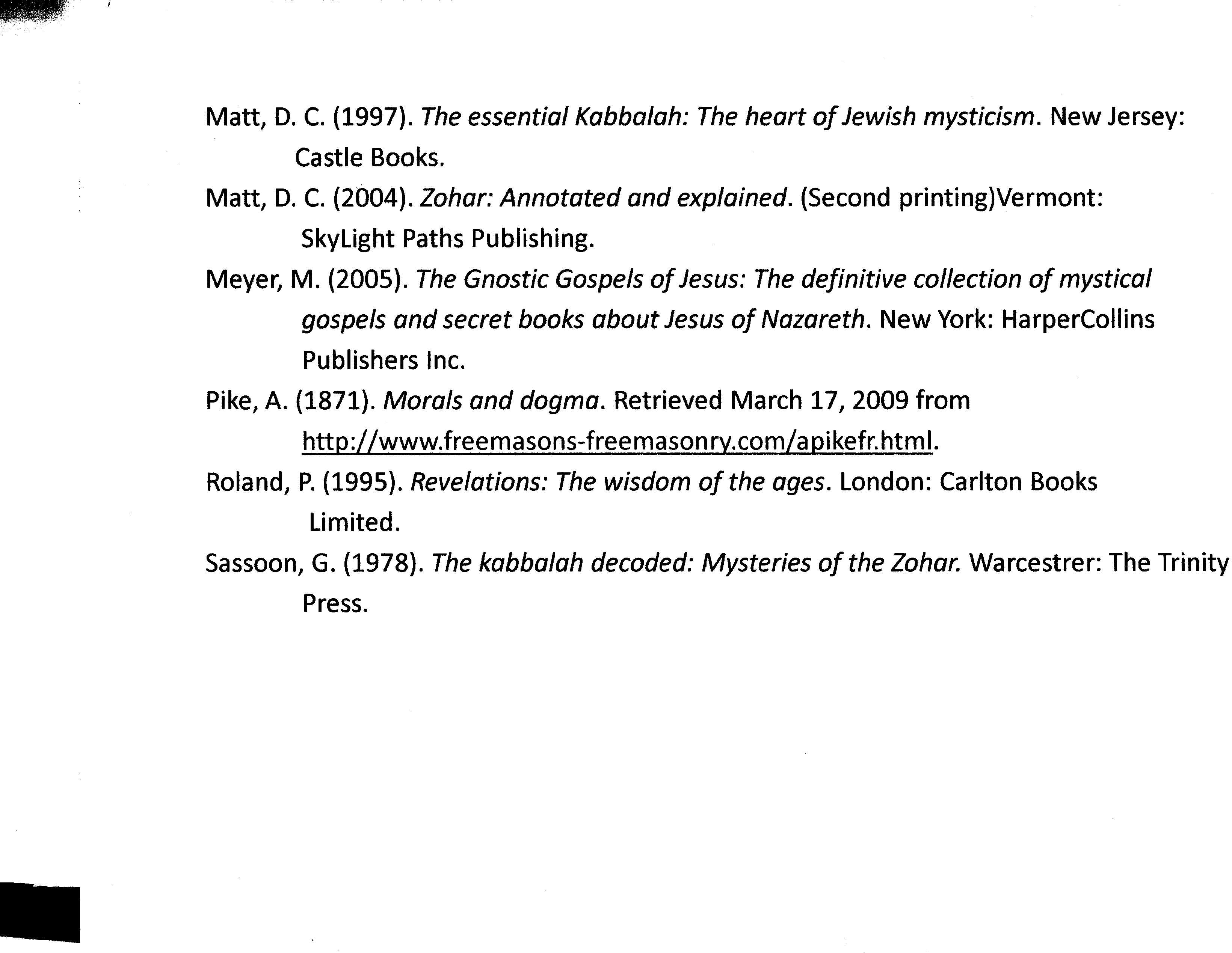

This section includes a paper about the subject-object dichotomy in Philosophy

Apocalypse

This section begins with a work that is a detailed analysis of the screenplay/poem found in the Art section of this site. This paper looks at the research behind the play that inspired its manifestation (or why I wrote the play). It is hard to avoid the Book of Revelations when the topic of the Apocalypse comes up, so the next paper in this section is a comparison of the similarities and differences of the Book of Daniel and the Book of Revelations. Many similarities were found and the research leads one to beleive that we are in the dawning of the Age when we will see great changes in the world as we know it today.

Solutions

This section includes papers on 3 pathways to happiness (physical, mental, emotional), followed by a paper on how to end prejudice, a paper on the polarization of the sexes is next (as it is hypothesized by this site that the true or pure unification of All That is in the Universe is solved by the reunification of the energy of the sexes ;). Finally, this section ends with an empirical thesis exploring the equal validation or rational and emotional styles.

Art/Screenplay

This section contains a play or screenplay called the Grand Drama that is written entirely out of prose (the owner and creator of this website has personally written everything that appears on it). This work of art reveals a hidden message, one that may unlock the key to the mysteries of the universe! This page also includes a shortened poem of the Grand Drama and provides a link to a song that is about Plato's Analogy of the Cave (members only).

Poetry

this is a collection of my poetry - enjoy!

Songs

This is a collection of my songs - enjoy! =)

Photos

This is my photo collection

Key to the Legend

Red = Philosophy

Blue = Physics

Yellow = mathematics

green = hard sciences

grey = psychology

the parts under construction are labeled as such or blanketed by <<< ____ >>> indicating personal notes to self to improve the site, or the layout of the information presented.

Recent Videos

Climate Anxiety, Mental Health and Children & Youth

Precarious Work in Violation of Human Rights: Corporations attain Human Rights while Humans become Commodities

The Pathways to Happiness: Through Positive Psychology

Integrated Intersectionality?

Prejudice: How Can We Stop It?

Dream Hospital: Revolutionizing the Health Care System

The Meaning of Life: Gnosticism and the Sacred Feminine

Breaking the Sex-Harm Link In Pornography

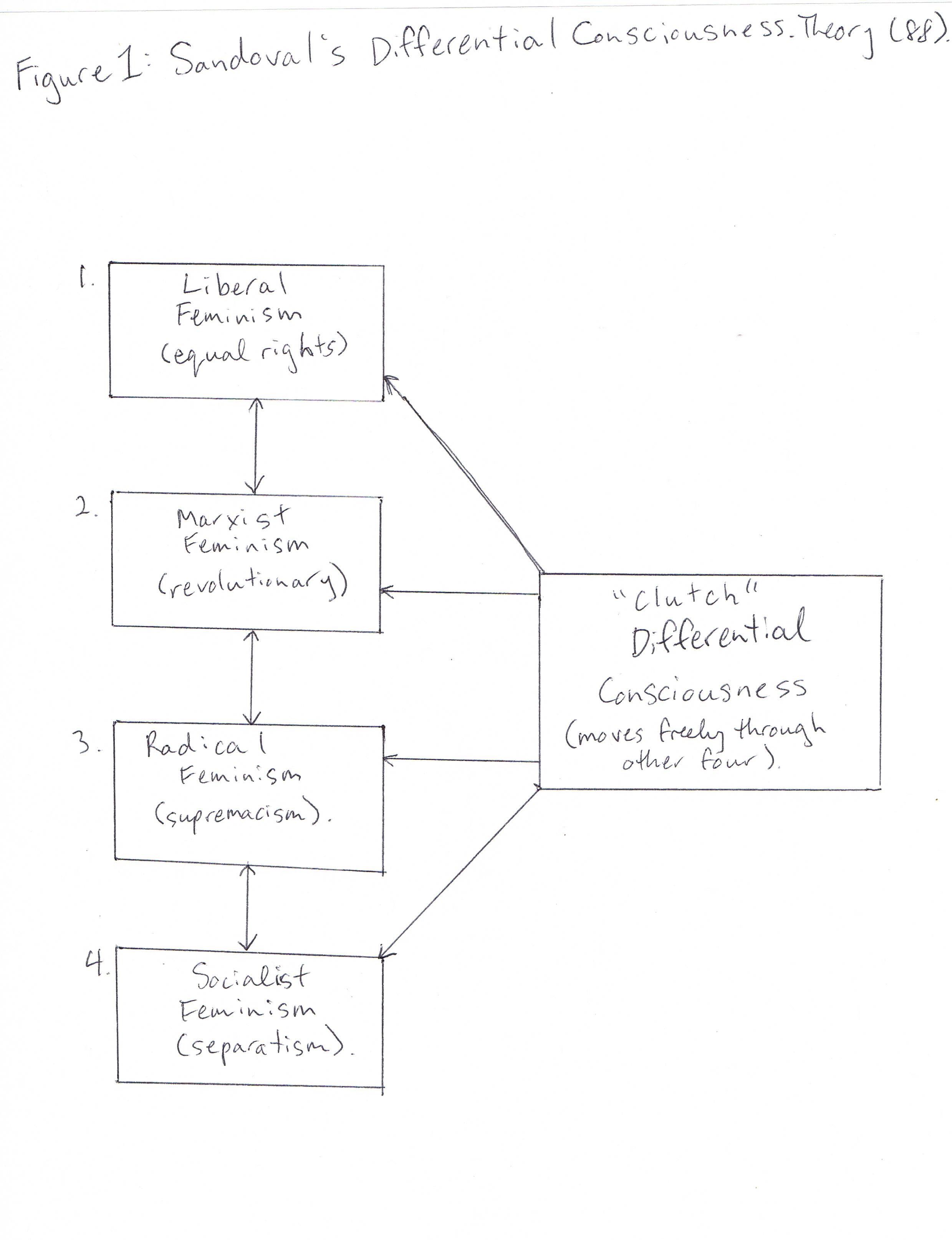

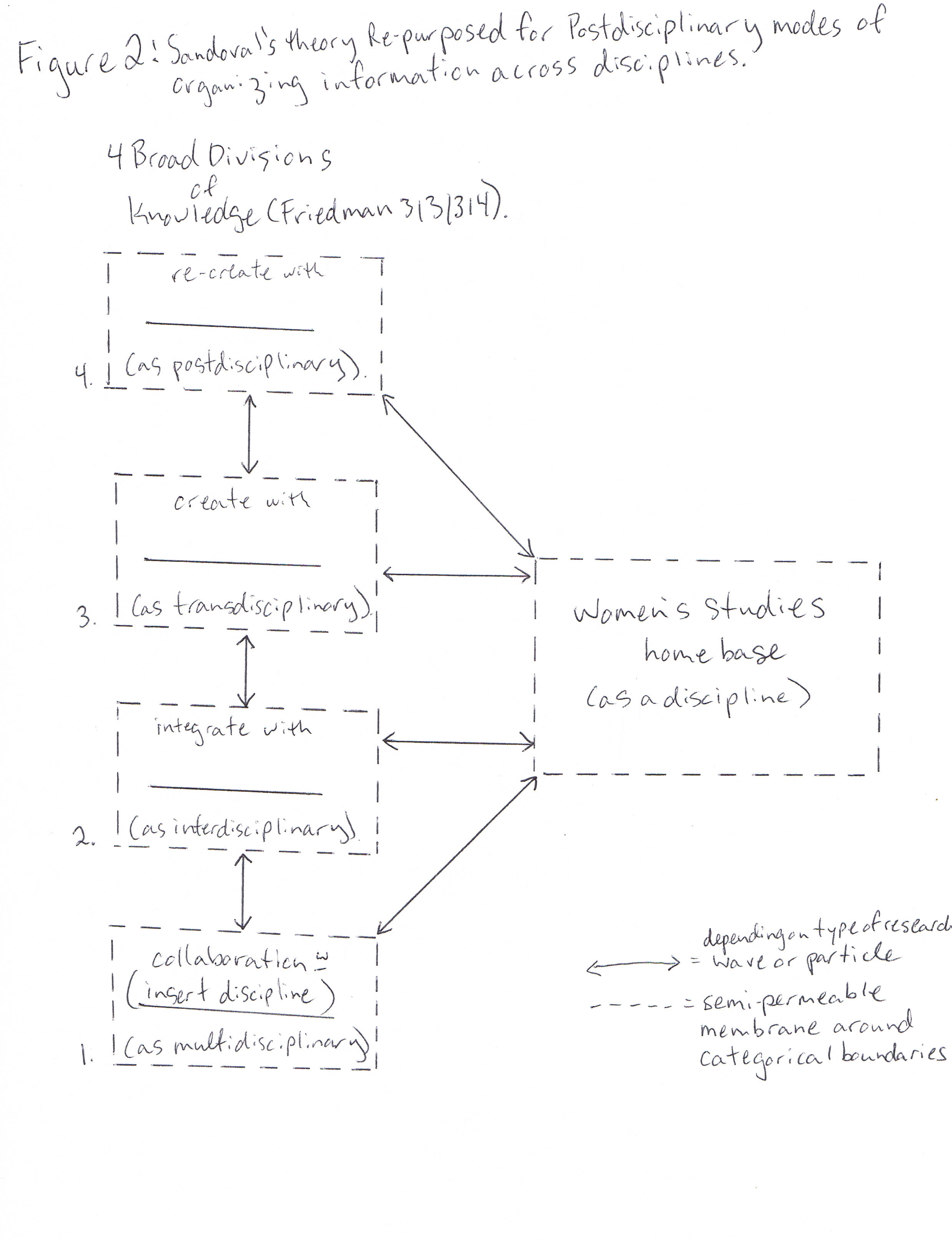

Interdisciplinarity and Women's Studies

The Importance of Equal Validation of Rational and Intuitive Cognitive Styles

Testing Plato's hypothesis that everything we've been taught is based on a false premise

Challenges in Community-University Collaboration

Climate

Anxiety and Mental Health in Child and Youth

Climate Anxiety, also referred to as Ecoanxiety is “anxiety or worry felt about climate change and its effects” (Clayton, 2020, p.3), or “dread associated with negative environmental information” which includes “uncertainty about the future environment, grief about the loss of valued places and things, and concern about possible future harm to one’s children” (p. 2).

Perceived Ecological Distress is “personal stress associated with environmental problems” (Clayton, 2020, p. 3). When it comes to children and youth, the term generation anxiety is used.

Which is “existential dread about what lies ahead…for millennial[s]” (Chisholm, 2019, p. 1). This includes “rising income inequality, bitter political polarization, precarious work and a rapidly warming planet” (p. 1). Global inequality and climate change are some of the worries.

Psychological wellbeing is influenced by climate change and there is substantial evidence showing that weather events and natural disasters impact mental health (Clayton, 2020; Masten, 2014). The groups most affected are Indigenous peoples, the elderly, and children (Clayton, 2020). According to Clayton (2020) “[t]here has been relatively little acknowledgement of the mental health implications of climate change” (p. 5). Research on how climate anxiety affects mental health shows increased levels of PTSD, depression, anxiety, substance abuse and even domestic violence.

Prevalence

America. Regarding prevalence, in America, Clayton and Karazsia (2020) found that about 17-27% of their online sample reported their ability to function was impacted by climate anxiety. A survey by the New York Times found that “25% of 1800 Americans said they expected to have fewer children than they considered ideal [and] of these, 33% cited worry about climate change” (Clayton, 2020, p.4). In 2018, emotional responses to climate change documented by the Yale Program on Climate Change Communication, found that “69% of Americans are at least ‘somewhat worried’ about global warming and 29% said they were ‘very worried.’ Almost half (49%) think they are personally going to be harmed by it” (p.3). In the same year, the “stress in America survey showed that 51% of respondents listed climate change as ‘a somewhat or significant source of stress.’ (p. 3) The American Psychological association conducted a survey 2020 and “found that two-thirds of respondents felt as least a little ‘eco-anxiety’…and about one-quarter of them said they felt a lot of eco-anxiety” (p. 3).

Australia. In Australia, 86% “reported some concern, and 20% reported feeling ‘appreciable distress’ associated with climate change” (p. 3). In this survey, 39% of the responders said that climate change was “the most serious problem facing the world in the future” (cited in Clayton, 2020, p. 3). Australian farmers experiencing climate change reported an increased self-perceived risk of depression and suicide” (p. 3). In Greenland a national survey reported that 38% experienced moderate to very strong fear, “19% reported moderate or strong sadness, and 18% reported moderate or strong hopelessness” (p. 3). In Tuvalu, an island nation experiencing noticeable effects of climate change, “95% reported distress from climate change” and impaired normal functioning in 87% of the cases (p. 3). In Canada increases in substance abuse and suicidal ideation was reported among Inuit peoples (p.3).

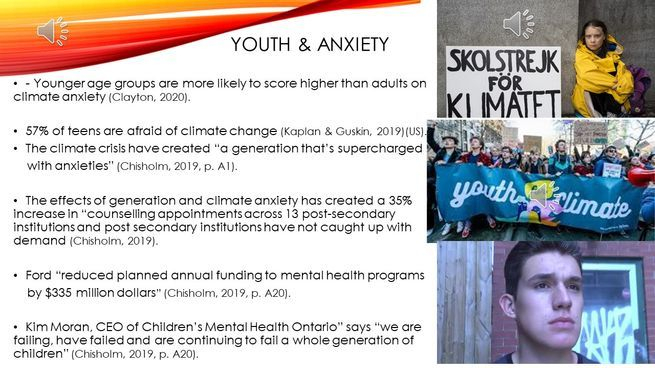

Youth & Climate Anxiety

Younger adults “experience the strongest effects” and are more vulnerable when climate change is a direct experience. Young adults are more likely to score higher in climate anxiety than older adults (Clayton, 2020, p.2). When it comes to extreme weather events, children and youth have, on average, stronger responses such as sleep disorders, depression, and PTSD (Clayton, 2020). When weather events occur, children are more vulnerable because of their dependence on parents and the likelihood that social supports are disrupted are increased (Bartlett, 2008). In the US in 2019, Kaplan and Guskin found that “57% of teens said they were afraid of climate change (as cited in Clayton, 2020, p. 4). Younger adolescents and young adults think more about their future than older adults (Clayton, 2020) and this could be impacting the degree of anxiety experienced by younger aged groups. For example, the Toronto Star exclaims that issues such as the climate crisis have created “a generation that’s supercharged with anxieties” (Chisholm, 2019, p. A1). One student reports his experience of anxiety as being “strongest on my heart…a feeling I don’t know how to explain, but it’s like tight or very heavy” (Wang as cited in Chisholm, 2019, p. A21). The effects of generation and climate anxiety has created a 35% increase in “counselling appointments across 13 post-secondary institutions and post secondary institutions have not caught up with demand. Students are reporting extremely long wait times for counselling. This is why it is shocking to hear that Ford “reduced planned annual funding to mental health programs by $335 million dollars.” Kim Moran, CEO of Children’s Mental Health Ontario” says “we are failing, have failed, and are continuing to fail a whole generation of children (Chisholm, 2019, p. A20).

Implications of a Warming Planet

It

is surprizing, the implications a rapidly warming planet can have on mental

health. For example, heat “has been consistently associated with aggression and

conflict and more recently has been found to correlate with increased rates of

suicide and of hospitalization for mental illness” (Miles-Novel et al.; Carlton,

2017; Obradovick et al., as cited in Clayton, 2020, p. 1). Climate change is

associated with pollution due to increased levels of particulate matter, ozone,

and carbon, and warmer air holds “higher levels of these pollutants” (Clayton,

2020, p. 2).

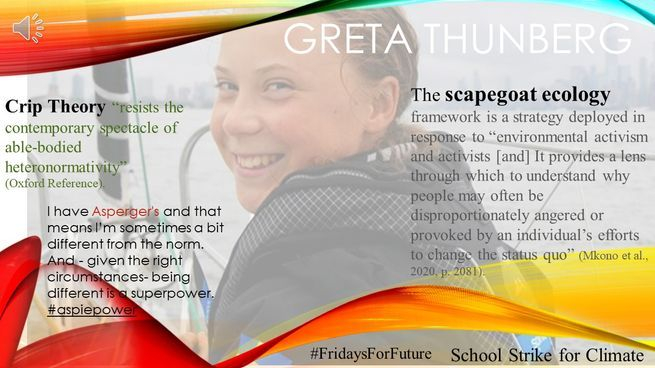

In 2018 Greta began striking at the Parliament buildings in Sweden with a sign that read "School Strike for Climate" (BBC News). Her cause became viral with her #FridaysForFuture strikes. This is not surprising considering the movement suggests students skip school. In September 2019, she set off on an environmentally friendly yacht to address a UN climate conference in New York. Greta refuses to fly because of the environmental impact. Graham & Metz, (2017) state that “By 2050, air travel is expected to quadruple and the price of this ”falls heavily on the shoulders of the planet, with scientists linking increasing global carbon dioxide emissions to climate change (Baumeister & Onkila, 2017; Becken, 2007).

Greta is an interesting example in climate anxiety and mental health because her advocacy for a clean planet creates mixed emotions (Mkono et al., 2020). The scapegoat ecology framework is a strategy deployed in response to “environmental activism and activists [and] It provides a lens through which to understand why people may often be disproportionately angered or provoked by an individual’s efforts to change the status quo” (Mkono et al., 2020, p. 2081). Greta, therefore, gets some backlash in her efforts and her Asperger’s is wielded as a weapon against the credibility of her cause. However, Greta is an exemplary spokesperson for mental health and de-stigmatization of mental illness because she refers to her Asperger’s as a “superpower” (BBC). Linking this to Crip theory, the term ‘crip’ emerged in disability movements, as an adaptation and reworking of the derogatory word ‘crip**’ (Oxford Reference). In Crip theory, taking back the name in an attempt to transform it from its pejorative connotations is a way for those with disabilities to insert and exert their voice into mainstream consciousness in order to “resist the contemporary spectacle of able-bodied heteronormativity” (Oxford Reference). Like queer theory disrupts by ‘queering things up,’ crip theory ‘crips things up’ and challenges dominant frameworks of disability. The positive embracing of Asperger’s as a part of herself could be considered a protective factor for mental health.

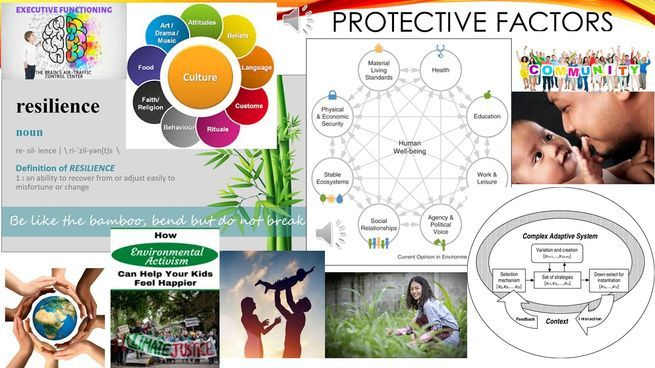

Protective Factors

Some other protective factors are resilience, good adaptation, social connections, and societal wellbeing (Clayton, 2020). For example, “human interdependence in young people who are resilient, flexible, have common attributes and connections to community support systems are important protective factors (Masten, 2014). Also, having an attachment figure close by during and after natural disasters is protective (Masten, 2014, p. 8), as well as good parenting (p. 10) and the development of “executive function skills” (Masten, 2014, p. 10).

Some say that validating, rather than pathologizing people’s emotional responses to climate anxiety can protect from negative effects (Clayton, 2020, p. 5). If one is not too severely distressed over climate change, then active engagement in climate resolution or doing their part can be a protective factor. “Doherty (2015) has emphasized the importance of empowerment, encouraging people who are experiencing climate anxiety [to] engage in [environmental] conservation actions [because it] can promote perceived efficacy and competence [leading] to an ‘adaptation-mitigation cascade’” (p. 208). [Adaptation-mitigation cascade means that mitigating] climate change facilitates adaptation to the threat. If one has not been directly affected by climate change, it is suggested that engagement in climate activism, could be considered a form of proactive or anticipatory coping (Reser et al., 2012).

Research shows positive correlations between happiness and environmental action (Corral-Verdugo, Mireles-Acosta, Tapia-Fonllem, & Fraijo-Sing, 2011; Howell & Passmore, 2013), and even those who perceive the threat from climate change as severe show reduced distress and depressive symptoms when they are involved in behavior to mitigate the problem (Bradley et al., 2014) (This is all from Clayton, 2020 p. 5).

Culture has been found to be a protective factor, including cultural rituals, and respect for indigenous community values important to their culture such as acts of reconciliation and forgiveness as promoted by the Mmi’kmaq indigenous peoples (Clayton, 2020, p. 12). Discussing protective factors, involves interaction between various complex systems involved, especially in adaptive systems. Developmental Psychopathology can be useful for studying the interaction of complex systems or how they “co-act to shape the course of development, across levels of function, from the molecular to the macro-levels of physical and sociocultural ecologies” (Masten, 2014, p. 9). Developmental psychopathology can use complex models to determine protective/risk factors and trajectories (Rutter Stroufe, 2000). So next I will discuss some risk factors.

Risk Factors

Some risk factors involved in eco-anxiety and exposure to natural disasters are again, the proximity of the attachment figure because if they are not present, trauma is increased (Cohen et al., 2009). For example, one girl was separated from her mother after Hurricane Katrina hit because it was her father’s weekend. She reports the trauma of getting to a local stadium where aid was set up and wished she were with her mother (Cohen et al., 2009). Depression after an environmental disaster increases the risk for “developing PTSD and related symptoms” (Cohen et al., 2009, p. 55) and chronic PTSD symptoms cause “cognitive and educational impairments, relationship problems, significantly increased health care usage, substance abuse, suicide attempts, and completed suicide” (p. 56).

The greater the exposure to the disaster (Cohen, 2009), “indexed by proximity to the epicenter of the devastation,” traumatic experiences are increased (Masten, 2014, p. 8). Children who live in disaster zones are likely to have experienced previous traumas and new disasters can activate previous PTSD symptoms (Cohen et al., 2009). There are sex and age effects because younger females are more vulnerable to the negative effects of natural disasters. Those who have been exposed to child maltreatment (Masten, 2014, p. 10), and children who have a predisposition for mental disorders and parental PTSD are also more vulnerable (Cohen et al., 2009).

Having to relocate after an environmental disruption also increases the risk of anxiety and PTSD. The riskiest group for developing greater symptoms are those who had family members die from natural disasters. Cohen et al. (2009) report that “children [who] had be relocated multiple times” and are not in their own homes are more likely to be exposed to adult behaviours such as “drinking, sexual activity, and violence” (p. 56). Masten (2014) states that “violence at the community level influences family function …[and] cascades to affect children” (p. 10). Another risk factor is lack of social assistance for children and “barriers to opportunity” (Masten, 2014, p. 12). Those who experience climate anxiety are “likely to be people who have strong connections to the natural environment” (Clayton, 2020, p. 5). This is why indigenous peoples are more likely to experience climate anxiety. However, “Going out on the land was seen not only as restorative… but as a way of participating in traditional culture which itself was a source of resilience” (p. 5). This is what made me want to explore culture as both a risk and a protective factor in my final paper. Next, I will quickly discuss some trajectories including mediating and moderating variables because the degree of development of negative symptoms from climate anxiety and natural disasters can be mitigated by certain factors.

Trajectories

Some trajectories or pathways climate anxiety can take include increases in migration and conflict (Clayton, 2020, p. 1). People may be forced to leave their homes not just from natural disasters, but from the effect of climate change such as “rising sea levels, thawing permafrost, melting glaciers, or desertification” (p. 1). For example, there are “significant levels of drought threatening the Great Barrier Reef… and wildfires [have] threatened communities and killed enormous numbers of iconic animals” in Australia (Clayton, 2020, p. 2). Migrating to different places can be very stressful, especially when moving to a different country. This can come with economic challenges and social conflict, especially if they are not welcomed by the new community, both of which are threats to mental health (Clayton, 2020). Clayton (2020) discusses how the home can facilitate resilience and when it is taken away, especially involuntarily, it can “threaten mental health” (p. 1). Solastagia, is a term used to “describe the chronic distress people experience in response to negative environmental change, particularly when it affects a home environment” (Clayton, 2020, p. 2).

Research shows there is a “possibility for long-term and/or permanent effects of early experience of trauma which can impair children’s ability to regulate their own emotions and can lead to learning or behavioural problems” (p. 2). Early stress can also increase the risk of mental health problems later in life (Clayton, 2020, p. 2). Doherty & Clayton (2011) found “intense emotions associated with observations of climate change effects worldwide and anxiety and uncertainty about the unprecedented scale of current and future risks” (p. 265).

If chronic worry about the environment and ecological anxiety is not dealt with, it can lead to a “potentially disabling response to risk” (p. 3) and can “interfere with a person’s ability to sleep, work, or socialize. As briefly discussed before, channeling the stress into doing something about the situation can be helpful and adaptive. However, individual differences in achieving this change of focus show that some may experience “ecoparalysis” which is “the inability to act on environmental challenges due to a perception that the are intractable” (Clayton, 2020, p. 2). When experiences of ecoanxiety, solastalgia and ecoparalysis are compounded, they create a constellation of mental health referred to as psychoterratic syndromes which are all associated with environmental damage and change (Albrecht, 2005).

If negative reactions to climate change are not based on direct experience, mediators affecting the degree of anxiety are social context and/or media (Clayton, 2020, p. 3). Norgaard, (2006) notes that because attitudes towards climate change vary across cultures, to a degree, climate change is socially constructed. So, culture and context mediate the degree of distress. This is why research should focus on the “role of context in moderating [or mediating] the influence of individual differences on adaptive function and development” (p. 14). Therefore, a suggestion for future research, would be to focus more on context and culture as a way to mitigate perceptions around climate change and anxiety.

Other factors that moderate the experience of climate anxiety are whether or not there is social assistance “and access to coping resources” (Clayton, 2020, p. 2). Age and resilience also moderate climate anxiety. When it come to accurate trajectories and predictions of the future, however, Clayton (2020) states that “no one can predict the exact impacts in a particular place and time (Clayton, 2020, p. 2).

Indigenous Knowledges

One of the groups most affected by climate change are indigenous peoples because they are more likely to be living in areas in danger from rising sea levels and melting (Clayton, 2020). According to Aboriginal understandings, the relationship of the human to the environment (and other animals and plants etc.) is reciprocal. Sylvia Moore (2017) discusses how we are part of the circle of life and connected to the trees, the water, and even the salmon. There is no separation between humans, animals, and the environment. If distinctions are made, however, then they are an I/We distinction and not an I/You contrast (Chilisa & Kawulich, 2012). This is different from Western understandings that tend towards binaristic thinking and antagonism between categories in a binary. Binaries and binaristic thinking are a product of the English language and thus affect our thinking and influence our world view (von Humboldt, 1836/1999; Whorf, 1956). Those who speak English, therefore, may have a propensity to think in binaries.

Aboriginal languages, such as the Hopi language do not set up the world to be in binaries, but rather, through their language, see the world as a unified whole (Whorf, 1956). For example, in the Hopi language, the same word for apple also means tree, and also means decay, capturing the cyclical motion of life (Whorf, 1956). The Maori peoples of New Zealand have a worldview based on the principle of Whakapapa which “turns the universe into a moral space where all things great and small are interconnected” (Denzin & Lincoln, 2008, p. 11). Similarly, Mi’kmaq “teachings are based on the interconnectedness of all things” (Marshall as cited in Moore, 2017, p. 24). These understandings see human beings as interconnected with the living world and therefore are emersed in many relations and connections (Chilisa & Kawulich, 2012).

In contrast, Western thinking tends to produce a linear, fragmented, and compartmentalized world where the sum of the parts equals the whole. This produces a mechanistic world view, as opposed to indigenous thinking that produces an organistic world view (Coole & Frost, 2010; Harris et al., 1977). Organistic thinking, also called ‘system thinking’ (Angyal, 1965), sees the world in terms of complex patterns with an implicit order of unification. This is somewhat in line with Developmental Psychopathology because it stresses the importance of dynamism and reciprocity and uses complex models (Cicchetti & Rogosch, 1996; Rutter & Stroufe, 2000; Stroufe & Rutter, 1984). But goes against traditional positivist understandings of reductionism and simple causation and against a mechanistic worldview that focuses on linear relationships and individual elements or parts (Harris et al., 1977). According to Coole and Frost (2010), “[h]ostilities between [mechanistic and organistic] approaches have traditionally been staged as an opposition between mechanistic and vitalist understandings of (dead versus lively) matter” (p. 9). As well as producing a short-sighted understanding of complex systems, mechanistic thinking objectifies the Earth. This objectification subsequently justifies the exploitation of the Earth and the unrestrained extraction of its resources for personal gain. Mechanistic thinking, therefore, is a slippery slope towards aggressive neoliberal exploitation of peoples and the Earth in the pursuit of profit.

Remember article 24 of the Convention of the Rights of the Child (CRC) that demands “clean drinking-water, [and the] taking into consideration the dangers and risks of environmental pollution” (United Nations Human Rights, 1998)? Well, this leads me to believe that climate change is, in part due, to neoliberalism and globalization. For example, “open-pit mining in Costa Rica uses the extremely toxic cyanide lixiviation technique, which has led to severe pollution and consequently to organized resistance among local communities” (Isla, 2002, p. 148). Clayton (2020) reports that “damage associated with mining in…Australia was associated with mental distress among local residents” (p. 2).

Aboriginal understandings of the Earth as a living, interconnected, organism feeds into their climate anxiety and “changes to the natural environment mandate changes in traditional practices (Clayton, 2020, p. 4). Perhaps the reason an indigenous or organistic world view is a risk factor is more due to their social positioning. For example, if the elites and those who have power in this world would adopt an indigenous, organistic worldview, they would be more likely to see the role of humans as stewards of the land, rather than conquerors of it. This is the analysis I will be posing in my final paper. It also begins to steer us towards solutions to climate change and climate anxiety.

Solutions/Ecotherapy

Similar to indigenous understandings, “Ecotherapy…stems from the belief that people are part of the web of life and that our psyches are not isolated or separate from our environment. Ecopsychology is informed by systems theory and provides individuals with an opportunity to explore their relationship with nature—an area that may be overlooked in many other types of psychotherapy” (Good Therapy, 2018). Research shows after completing a 40-minute cognitive task designed to induce mental fatigue, the participants, who had walked in the nature preserve reported “less anger and more positive emotions than those who engaged in the other activities” (Good Therapy, 2018). An experiential example from someone who went through Ecotherapy reports, “I remember walking into the garden, and I immediately felt better…There was food growing, and flowers. It really helped to shift my thinking” (Smith as cited in Hamblin, 2015). In another study “a nature walk reduced symptoms of depression in 71% of participants, compared to only 45% of those who took a walk through a shopping center” (MIND, 2007). Chalquist (2009) found that if you hold soil bacteria called Mycobacterium vaccae in your hand for 20 minutes, it can improve one’s mood. In more recent studies, Mycobacterium vaccae, has been suggested as a vaccine after showing “good protection in mice against tuberculosis” (Gong et al., 2020).

Even though the idea of Ecotherapy should be credited to Shamanism and is more commonly credited to Henry David Thoreau’s in his 1864 The Main Woods, Ecotherapy as a profession, is considered fairly new (Hamblin, 2015). There are skeptics that demand the practice should be standardized and be subjected to “licensing requirements.” They also say it should not be “a replacement for standard evidence-based treatments” (Hamblin, 2015). After hearing about the experiments with soil bacteria, Hamblin (2015) quips “ask your doctor before replacing your psychoactive medications with dirt.” Since Ecotherapy brings in elements of indigenous knowledge, ecology, biology, sociology, and psychology, it could be considered a transdisciplinary venture.

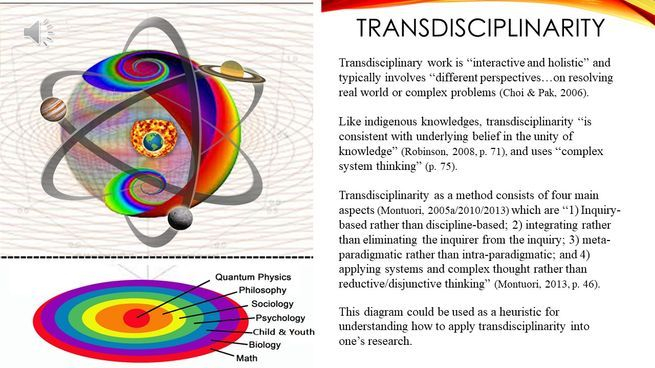

Transdisciplinarity is an emerging research practice that is gaining momentum and notoriety and could be said to a ‘buzzword’ when it comes to graduate work. Transdisciplinarity integrates many disciplines and a good example of this is the broad discipline of sustainability which integrates “politics, economics, philosophy…social sciences as well as the hard sciences” (Arizona State University; Robinson, 2008). It promotes renewable resources, alternative energies, and new modes of transportation. This could address the real-world problem of climate anxiety and ease the mind of Greta Thunberg and the like who suffer from its negative effects. The idea of a healthy, sustainable planet lends itself well to transdiciplinarity because it demands an activist or social justice component (Pycroft & Bartollas, 2014). Transdisciplinary work is “interactive and holistic” and typically involves “different perspectives…on resolving real world or complex problems (Choi & Pak, 2006). Like indigenous knowledges, transdisciplinarity “is consistent with underlying belief in the unity of knowledge” (Robinson, 2008, p. 71), and uses “complex system thinking” (p. 75).

Transdisciplinarity can be used as

a method in itself and is said to consist of four main aspects (Montuori,

2005a/2010/2013) which are “1) Inquiry-based rather than discipline-based; 2)

integrating rather than eliminating the inquirer from the inquiry; 3)

meta-paradigmatic rather than intra-paradigmatic; and 4) applying systems and

complex thought rather than reductive/disjunctive thinking” (Montuori, 2013, p.

46). I use transdisciplinarity as a methodology by compiling research examples

from many disciplines and use them as converging evidence, which is

meta-paradigmatic and produces a well-rounded case. An example of how I

integrated various disciplines in my last paper is shown here on the slide.

This diagram could be used as a heuristic for understanding how to apply

transdisciplinarity into one’s research.

CONCLUSION

In this paper, climate anxiety research demands a well-rounded case and argues that context, culture, and complex systems be used when exploring eco and climate anxiety. Therefore, transdisciplinarity lends itself well to climate anxiety research because it does not stop at the ‘what and how’ descriptions of climate anxiety and its effects but allows for a paradigm shift in pooling disciplinary knowledge together to find real world solutions, like Ecotherapy.

Precarious Work in Violation of Human Rights: Corporations attain Human Rights while Humans become Commodities (SLIDE)

Freud once said that “Love and work are the cornerstones of our humanness.” But, I fail to see how life or humanness is this simple. In my experience as a single mother engaged in precarious work, I have found a distinction can be made between creative, enjoyable work and necessary work (Lowe, 2015; Tremsness, 2016). The work I call necessary lacks control and creativity and has become increasingly dehumanized. (SLIDE)

In 1844 Marx discussed two main critiques of capitalist labour saying that it created alienation and was exploitive (Lowe, 2015). Marx’s concept of commodity fetishism discusses how the value of labour has been dehumanized by only seeing value as in the product itself (Tromsness, 2016). This has the effect of turning the product into the subject and the human subject into an object. Hence the title of my project. (SLIDE)

On an international level, in the 1970’s, neoliberalism and globalization began to create a new employment climate due to austere capitalist social and economic thinkers that increasingly saw the world as an open market (Standing, 2016). Neoliberal ideas consisted of convincing companies that reducing worker securities, such as benefits, and de-industrialising unions would stall the rise of unemployment and poverty and if they did not put these changes into place, then “economic growth would slow down, [and] investment would flow out” (Standing, 2016, p. 6). However, what it did was produce more insecurity and poverty, which trickled down to all levels of society with serious consequences. Neoliberal attitudes place the onus of survival onto the individual, relieving the state of responsibility. (SLIDE)

This project will show the ubiquity of precarious work. I will argue that precarious work is dehumanizing and exploitive to the point that it violates human rights. Precarious work is responsible for negative health effects and contributes to the feminization of poverty. I desire to make jobs less precarious on local, provincial and national levels. First, I will define precarious work, then show how it violates human rights and on what grounds. On both a provincial and federal level, suggested remedies for the negative effects caused by precarious work will be discussed. (SLIDE)

Precarious work is described by contract work, that is part-time, has little-to-no benefits (Standing, 2016), and has little chance for advancement (Gazso, 2010). Precarious employment contains elements of “uncertainty, insecurity and lack of control” (Lewchuck et al., 2015, p. 14) and are considered to be jobs that do not fall under the “Standard Employment Relationship” (SER) which are jobs defined by security, provide a “full range of benefits and [have a] possible career path” (Lewchuck et al., 2015, p. 10). Precarious jobs are dead end, come with reduced job and life opportunities, are demeaning, alienating and considered “not big enough for the human spirit” (as cited by Allan, Bamber, & Timo, 2004, p. 405). Precarious work is increasing on a global scale (Standing, 2016) and the unstable work environment has become the new norm in Canada (Canada without Poverty, 2017). (SLIDE)

The group most affected by the exploitation and dehumanizing effects of precarious work are women: particularly those with children and women of colour. The fact that the trend of precarious work negatively affects these groups disproportionately is why precarious work can be considered in violation of Human Rights on the grounds of sex, family status and ethnicity. (SLIDE)

Discrimination via Sex

Precarious work leads to discrimination on the grounds of sex because precarious jobs are held disproportionately by women (Shaw & Lee, 2012; Bose & Whaley, 2012; Young, 2010). Women in Canada work “30 hours per week less than men” (Moyser, 2017). In the year 2000, 47% of Canadian women’s jobs were precarious compared to 27% of men’s jobs (Wallis & Kwok, 2008). In 2007, “almost half a million part-time temporary employees were women whereas just over a quarter of a million were men” (Vosko & Clark, 2009, p. 29). In 2015, 18.9% of Canadian women were engaged in part‑time (precarious) work, compared to 5.5% of employed men (Moyser, 2017).

The disproportionate streaming of women into precarious jobs creates the wage gap. In 1999 “women earn[ed] an average of 74 cents for every men’s dollar” (Bose & Whaley, 2012). Statistics Canada said in 2015, women made 87 cents to every man’s dollar (Moyser, 2017). The degree of gap, however, varies depending on where they work (Moyser, 2017). For example, in 2006, Hamilton women made 62 cents to the man’s dollar (Shaw, 2006). This report also stated that Canada has the fifth largest wage gap out of 29 developed countries (Shaw, 2006). Precarious work also leads to the glass ceiling, which is the little chance of advancement in the workplace. This, of course is not an exhaustive list and are only some of the reasons why precarious work leads to the feminization of poverty. More women than men experience a time crunch where it feels like both work and domestic duties cannot be completed in time, or done well (Gaszo, 2010). The “double day” of juggling domestic and work-related duties, creates stress and leads to depression and other negative effects such as exhaustion and burn-out (Gazso, 2010). (SLIDE)

Research finding a link between precarious work and overall negative health is robust (Lewchuk, Clarke, & deWolf, 2008; Young, 2010) and can also be responsible for suicide (Standing, 2016). Precarious jobs also contribute to heart disease, hypertension, gastric problems, (Gasper, 2012). Dissatisfaction of work can cause pain, fatigue, anxiety, depression, frustration, tension, problems sleeping and headaches, whereas more permanent work led to less chronic illness and better overall health (Lewchuck et al., 2008). Since women are more likely to engage in precarious work, women are more likely to experience negative health effects. (SLIDE)

Discrimination via Family Status

Another violation of Human Rights is on the grounds of family status due to something called the “family penalty,” in which child-care affects the ability to engage in paid work (Gazso, 2010, p. 230). Childcare is the major reason for women taking part-time work in Canada (Moyser, 2017). This can include the increasing number of children staying at home for longer periods of time due to the inability to find jobs or find jobs that pay enough to move out (Burke, 2017). The family penalty can also include those described by the “sandwich generation” who are placed in dual care-giving roles of both younger and older generations (Burke, 2017, p. 3). Statistics Canada (2010) reported that 30 percent of Canadians aged 45 to 64 are simultaneously responsible for their children under 25 and their aging parents (Burke, 2017, p. 4). Two-thirds of Canadian parents said they were dipping into their savings to care for older children staying at home (Burke, 2017). Due to these factors, some women either engage less with paid work or quit their jobs altogether (Burke, 2017; Shaw & Lee, 2012). The ability to save money is hindered by caregiving responsibilities, having lower savings and retirement money than men and by the time women are ready to go back to work, they may have been deskilled in the process (Burke, 2017). (SLIDE)

The lack of effective national child-care has been said to be the major factor in why women have difficulty balancing work and domestic responsibilities (Gazso, 2010). In Canada, we have yet to establish effective national child-care (Wallis & Kwok, 2012).

Wallis and Kwok (2008) state that “[s]tructural poverty is a violence” (p. 9) and that the feminization of poverty is due to policy changes around Employment Insurance (EI), welfare assistance, and lack of social support (Gazso, 2010). Changes in EI, from what used to be called Unemployment Insurance (UI) disadvantaged women when eligibility for leave became determined by the number of hours worked, rather than weeks worked (Gazso, 2010). Not only were less women eligible, but maximum compensation for leave went from 60% of previous earnings to 55% (Gazso, 2010). In Canada, there is a weak safety net for families requiring assistance (Gazso, 2010). All these factors, plus many more, contribute to the feminization of poverty (Wallis & Kwok, 2008) and affect health negatively (SLIDE)

Discrimination via Racialization

In the workplace, even though it is illegal to discriminate based on ethnicity and sex, it persists (Bose & Whaley, 2012). Racialized women, particularly immigrants “experience the worst labour market conditions and outcomes” (Premji, Shakya, Spasevski, Merolli, & Athar, 2014, p. 123). Racialized women are overly represented in precarious jobs that are high risk (Law Commission of Canada, 2012), non-standard and receive low pay (Gazso, 2010). Women of colour experience more discrimination in hiring and employment opportunities due to their gender, ethnicity and class (Premji et al., 2014; Gazso, 2010; Clement, Mathieu, Prus & Uckardesler, 2009; Gupta, 2009) than white Canadian-born women (Gazso, 2010). Non-whites and immigrants experience systemic discrimination due to the devaluing of their education, lack of access to professional training, language barriers and the demand for vaguely defined “Canadian experience” (Gupta, 2009, p. 147). (SLIDE)

I place this project into the realm of Social Justice because human rights are a social justice concern. Though there is no agreed upon universal definition, the general definition is “Justice in terms of the distribution of wealth, opportunities, and privileges within a society” (Dictionary.com). Scholarly articles describe social justice as a moral imperative and demand that “Individuals and groups…receive fair treatment and an impartial share of the benefits of society” (Hemphill, 2015, p. 1). Social justice can also be a global movement defined as “the way in which human rights are manifested in the everyday lives of people at every level of society” (Edmund Rice Centre, 2000, p. 1). The United Nation’s (2006) definition is “the fair and compassionate distribution of the fruits of economic growth” (p. 16). Because the distribution of economic wealth is not proportionate or fair to women, especially mothers and women of colour, we can see that precarious work is in violation of human rights an is in need of social justice. (SLIDE)

Going up against the Government of Canada, however, has only been done successfully once in October 2014 regarding the National Child Welfare case which led to the Truth and Reconciliation Act. It is good news that there is precedence, however, a great deal of research and statistics would be involved in filing a case about precarious work at the Human Rights Tribunal of Canada or the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario. Therefore, my project will gather as much data as possible to show that similar patterns affect women on all levels of society by showing that it happens right here in the Niagara Region. It will also seek out particular struggles in order to suggest policy changes on a provincial level and social services on a federal level. (SLIDE)

Collaborating with the Poverty and Employment Precarity in Niagara (PEPiN) project, I can show that even on a local level, there are similar patterns to Canada-wide statistics. Analyzing the PEPiN (2017) random digit dial phone survey dataset, 57.1% women reported anxiety produced from the uncertainty of the work schedule interfering with socializing with both friends and family, compared to 42.9 % of men (n = 710, 3 = missing). Analyzing this further to determine if there was a significant difference between men and women in the Niagara Region, a chi square test of independence was conducted. A significant difference between men and women’s reported anxiety was found X² (df = 3, n = 708, 5 = missing) = 9.059, p = .029. (SLIDE)

The PEPiN project also conducted an on-line survey at the beginning of 2018, that asked “How has precarious employment impacted you?” One respondent said they had” [c]onstant anxiety over if [they] can afford living, [and had to] hold off starting a family” (p. 67). Another respondent said, “In Niagara there is always this fear that we could potentially lose our job especially being a woman, so I try my best to put a smile on even though I am mentally and physically exhausted most days” (p. 60).

A lot of respondents complained of the unpredictability of the work, unpredictable scheduling, and 44% asked for more job security. All 71 respondents (N = 71, 60 = female, 8 = male, 1 = gender neutral, 1 = missing) said that money in some way was the biggest challenge when dealing with precarious work including inability to pay bills, save, pay a mortgage, or a car loan, make ends meet, “save for retirement and education funds for [their] kids” (sic) (p. 21), difficulty paying medical expenses, and lack of benefits. Some respondents asked for more paid sick days. (SLIDE)

Precarious work is a serious issue and due to its negative effects should not be allowed to be the “new norm in Canada.” One respondent wished for “somehow stopping companies from using loopholes, [have] better legislation, [and] basic income. There's so many people in precarious work that we would have the power to force change but we're all too busy working multiple jobs for little money that people feel powerless…We need to help the people of these communities, it's like those in power are so far separated and privileged they have no idea what most are going through. (PEPiN, 2018, p. 30) (SLIDE)

Taking the research and responses into consideration, if a case is filed at the Human Rights Tribunal of Ontario, remedies on a provincial level would demand more paid sick days, more predictable schedules and make schedules available at an earlier timeframe to help balance more than one part-time job and/or help balance family and work responsibilities. Policies could also demand “[s]tricter laws for more mandatory hours” (p.33) or more stable work hours and more notice for layoffs. We also need policies that create “[m]ore good quality jobs (full-time, [have] benefits, [are] permanent, with pay we deserve” (p. 52). Benefits are important to workers, 51% of the respondents in the Niagara Region asked for benefits.

Lowering the cost of living was also suggested as a remedy. One respondent said that “raising the minimum wage was stupid because employers are cutting hours at every corner. What we should be doing is lowering the cost of living…” (p. 37). Since each province has their own tax system, perhaps less taxes could be added to goods and services. Policies that inform employers about the various disadvantages to women and the negative health effects involved could help workplaces compensate for the negative effects that come with precarious work. Suggestions include daycare facilities at workplaces, shift sharing, where many women can split the shift times depending on their availability. Also, a new understanding of when and where work needs to be done could allow more women to work at night and/or from home. (SLIDE)

If a case against precarious work is to be filed at the Canadian Human Right Tribunal, remedies on a federal level would demand more social services such as federally-funded universal childcare, easier access to EI and welfare. Also, easier access to professional training, language classes and the demand for a more specific and detailed definition of “Canadian experience” would benefit women of colour, immigrants and migrant workers. (SLIDE)

This project has shown the ubiquity of precarious work and how it adversely affects women, especially mothers and women of colour in Canada. There certainly seems to be a strong case against the federal and provincial government to get better social services and create policy changes regarding work making work less precarious. (SLIDES)

References

Allan, C., Bamber, G. J., & Timo, N. (2004). Fast-food work: Are McJobs satisfying? Employee

Relations, 28(5), 402-420. doi: 10.1108/01425450610683627

Bose, C. E., & Whaley, R. B. (2012). Sex segregation in the U.S. labor force. In V. Taylor, N.

Whittier, & L. J. Rupp (Eds.), Feminist frontiers (pp. 197-205). New York, New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Canada without Poverty (2017). Un- and under-employed: The “new normal” of precarious

work. Retrieved from http://www.cwp-csp.ca/2017/04/un-and-under-employed-the-new-

normal-of-precarious-work/

Clement, W., Mathieu, S., Prus, S., & Uckardesler, E. (2009). Precarious lives in the new

economy: Comparative intersectional analysis. In L. Vosko, M. Macdonald, & I.

Campbell (Eds.), Gender and the contours of precarious employment (pp. 240-255).

London, Canada: Routledge.

Hemphill, B. (2015). Social Justice as a Moral Imperative. The Open Journal of Occupational

Therapy, 3(2), 1-7.

Human Rights. (n.d). United Nations. Retrieved from http://www.un.org/en/sections/issues-

depth/human-rights/

Gasper, P. (2010). Capitalism and alienation. International Socialist Review (74), 24-29.

Gazso, A. (2010). Mothers’ maintenance of families through market and family care relations. In

N. Mandell (Ed.), Feminist Issues: Race, class, and sexuality (pp. 219-246). Toronto,

Canada: Pearson Canada.

Gupta, T. D. (2008). Racism/anti-racism, precarious employment, and unions. In M. A. Wallis,

& S. Kwok (Eds.), Daily struggles: The deepening racialization and feminization of poverty in Canada. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

Law Commission of Ontario (2012). Vulnerable workers and precarious work. Toronto, Canada: Law Commission of Ontario.

Lewchuck, W., Clarke, M., & DeWolff, A. (2008). Working without commitments: Precarious

employment and health. BSA Publications Ltd, 22(3), 387-406. doi:10.1177/0950017008093477

Lewchuck, W., Laflèche, M., Procyk, S., Cook, C., Dyson, D., Goldring, L., … Viducis, P.

(2015). The precarity penalty: The impact of employment precarity on individuals,

households and communities―and what to do about it. [Adobe Digital Editions Version]

Retrieved from https://www.unitedwaytyr.com/document.doc?id=307

Lowe, D. (2015). Karl Marx’s Conception of Alienation. Retrieved from

https://1000wordphilosophy.com/2015/05/13/karl-marxs-conception-of-alienation/

Malitz, Z. (2012). Beautiful trouble. New York, New York: OR Books.

Moyser, M. (2017). Women and paid work. (Report No. 89-503-X). Ottawa, Canada: Statistics

Canada.

Premji, S., Shakya, Y., Spasevski, M., Merolli, J., & Athar, S. (2014). Precarious work

experiences of racialized women in Toronto: A community-based study. Just Labour: A

Canadian Journal of Work and Society, 22, 122-143.

Shaw, S. (2006). Women and poverty in Hamilton. Retrieved from the Social Planning and

Research Council of Hamilton www.wesley.ca/cmfiles/SPRCWomen&PovertyReport.pdf

Shaw, S. M., & Lee, J. (2012). Women’s voices: Feminist visions. New York, New York:

McGraw-Hill.

Social Justice. (n.d). In Dictionary.com. Retrieved from

https://www.google.ca/search?q=social+justice+definition&ie=utf-8&oe=utf-

8&client=firefox-b&gws_rd=cr&dcr=0&ei=QTewWrvXFMuI0wL6zqWoBw

Standing, G. (2016). The precariat: The new dangerous class. London, United Kingdom:

Bloomsbury Academic.

Tromsness, R. (2016). A summary of the “fetishism of commodities.” Retrieved from

https://owlcation.com/social-sciences/Analysis-of-Marx-The-fetishism-of-commodities

Wallis, M. A., & Kwok, S. (2008). Daily struggles: The deepening racialization and

Feminization of poverty in Canada. Toronto, Canada: Canadian Scholars’ Press Inc.

Young, M. C., (2010). Gender differences in precarious work settings. Relations Industrielles /

Industrial Relations 65(1), 74-97.

The Pathways to Happiness: Through

Positive Psychology

The Pathways to Happiness

Happiness is a rather difficult concept to define but intuitively, not only does everyone have an idea about what happiness is, but they also strive to have it in their life. Happiness can also be referred to as subjective well-being and/or life satisfaction (Peterson, 2006). Subjective well-being could also be defined as the combination of happiness and life satisfaction (Myers, 2000). Happiness, or subjective well being involve how the individual perceives him or herself to be and life satisfaction is how contented or fulfilled one is in their life. This paper will help those who are looking for happiness, find it more easily by discussing the three major pathways to happiness (or subjective well-being). The three major pathways are (1) Hedonia, which refers to pleasure and enjoyment (2) Engagement which refers to involvement or immersion in activities and (3) Eudaimonia which is the idea of finding meaning in life (Peterson, 2006; Personal communication, S. Sadava,

Pathway of Hedonia

Hedonism is the experience of increasing physical pleasure or enjoyment and minimizing pain (Peterson, 2006). Increasing physical pleasure can be achieved by satisfying or fulfilling sex and/or hunger needs (Oishi, Schimmack & Diener, 2001). The idea of Hedonia implies that happiness can be found in the activities in which an individual finds the most enjoyment. Research has shown that physical pleasure can increase daily reports of life satisfaction, especially if the individual seeks pleasure during that day (Oishi et al., 2001). Happiness produced by physical pleasure can be moderated by a certain personality characteristic. Oishe et al. (2001) have found that those who are high in sensation seeking are more likely to find happiness through physical pleasures. Thus, an individual is likely to display risk taking behaviour when after stimuli that is exciting and novel (Oishe et al., 2001), Therefore, people who search pleasure are more likely to find happiness through physical pleasure.

The concept that happiness can be reached by increasing physical pleasure and decreasing pain was taken up by the Epicureans as an ideology to improve the self (Oishe et al. 2001). This too is the contemporary implication of studying happiness. However, the contemporary view of the Epicureans is misinterpreted as over-indulgence of pleasure to the point of gluttony or sin (Oishe et al. 2001; Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). The actual idea of the Epicureans was to balance out the lows and the highs of pleasure and pain to reach the feeling and the understanding of the “power of the now” which produces a quiet bliss accompanied by the experience of the “immediate presence of existence” (Personal communication, H. Hunt,

Pathway of Engagement

Flow produced from engagement has been found to be inwardly rewarding (Keller & Bless, 2008) and has shown that if an individual’s activities can produce a state or experience of flow, then happiness can result (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). The key to achieving flow is finding a balance between too much control and too little control over what one is doing. (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). The idea of flow is not to exert too much in control because flow ensues from an effortless or spontaneous state and it is through this spontaneous effortless type of flow that one can find happiness (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999). It has also been found that the flow experience is more likely reached when skill and challenge are balanced (Peterson, 2006).

Flow can be found in a number of different activities such as creativity including music, art, sports, and games. The experience distorts the passing of time and can create a feeling of oneness with the universe (Csikszentmihalyi, 1999; Peterson, 2006). From personal experience, flow from writing songs on the guitar brings the most happiness. Sometimes it feels like the song writes itself by flowing out through me, or like the song has always existed in the ether of the universe and all that was needed to be done was to grab it and bring it down into the material world. It seemed as though the song was written in three minutes, even though a half hour had gone by. It is these experiences that can produce happiness from flow.

Flow can also be reached from doing work. Job-related stress is so prevalent in society that it has been increasingly recognized in health literature (Howard, 2008). This is good news for those who feel they hate their jobs because if flow can be achieved even on an assembly line in a factory, the benefit of happiness can result (Personal communication, S. Sadava,

Pathway of Eudaimonia

Eudaimonia is cultivating one’s inner self (Peterson, 2006) or finding happiness through the discovery of one’s “true potential” (Ryff & Singer, 1998). It is essentially about finding meaning in life (Personal communication, S. Sadava,

Spirituality is different from religion in that the former is a subjective, first hand experience whereas the latter is more formal and includes rituals, ceremonies (Personal communication, S. Sadava,

These pathways to happiness can be used as an ideology to help individuals increase happiness, subjective well-being and life satisfaction. The high sensation seeker can use physical pleasure as a means to happiness, the individual unhappy with his or her job can strive to attain flow at work to increase happiness, and happiness can be increased by finding meaning in life through spiritual and/or religious practices.Therefore, happiness can be found on a physical, mental and emotional level. And perhaps if one wanted to explore this further, there may be different combinations of physical, mental and emotional that can create higher levels of happiness. But, whatever the path you choose, please enjoy... =)

Word Count: 1,132

References

Batson, C. D., & Stocks, E. L. (2005). Religion and prejudice. In J. F. Dovidio, P. Glick

& L. A. Rudman (Eds.), On the nature of prejudice (pp.413-427). Austrailia: Blackwell.

Csikszentmihalyi, M. (1999). If we are so rich, why aren’t we happy? American Psychologist,

54, 821-827.

Howard, F. (2008). Managing stress or enhancing well-being? Positive psychology’s

contributions to clinical supervision. American Psychologist, 43, 105-113.

Maclean, M. A.,

Identity integration, religion, and moral life. Journal for the Scientific Study of Religion,

43, 429-437.

Myers, D. G. (2000). The funds, friends, and faith of happy people. American Psychologist, 55,

56-67.

Oishi, S., Schimmack, U., & Diener, E. (2001). Pleasures and subjective well-being. European

Journal of Personality, 15, 153-167.

Peterson, C. (2004). A primer in Positive Psychology.

Ryan, R. M., Rigby, S., & King, K. (1993). Two types of religious internalization and their

relations to religious orientations and mental health. Journal of Personality and Social

Psychology, 65, 586-596.

Ryff, C. D., & Singer, B. (1998). The contours of positive human health. Psychological Inquiry,

(9), 1-28.

Watson, P. J., Morris, R. J., Hood, R. W., Millron, J. T. Jr., & Stutz, N. L. (1998). Religious

orientation, identity, and the quest for meaning in ethics within an ideological surround.

International Journal for the Psychology of Religion, 8, 149-164.

Integrated Intersectionality?

Sandra Kroeker

SJES 5P02

November 29, 2017

Integrated Intersectionality?

Intersectionality, coined by Kimberlé Crenshaw (1989/1991), is an important tool for understanding how power intersects with certain traits such as sex, gender and ethnicity. Intersectionality is “the interconnected nature of social categorizations such as race, class, and gender as they apply to a given individual or group, regarded as creating overlapping and interdependent systems of discrimination or disadvantage” (dictionary.com). Originally developed to understand how oppression can become compounded, intersectionality has been used to understand how law, policies and work jockey to further oppress and discriminate minority groups; especially those who embody many minority characteristics at once. For example, an older, Black lesbian woman of low socio-economic status (SES), with a disability would be exposed to more (compounded) oppression than, a Black, middle-class heterosexual woman. Yet, a Black middle-class heterosexual woman would be exposed to more oppression and discrimination than a white woman of low SES and she would experience more oppression than a white middle-class man. The power dynamics that create compounded oppressions are therefore complex and in need of a heuristic or metaphor for better comprehension (Garry, 2015); especially in court and at work (Crenshaw, 1991).

Gender Studies research has suggested many metaphors to describe intersectionality (that I will discuss later in the paper) and traditional sciences and social sciences have taken up the task of looking at these different embodied characteristics seperately (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013). This is referred to as single-axis thinking. Looking at these embodied traits separately does an injustice to those who experience compounded oppression and discrimination. Therefore, intersectionality is also an important heuristic for countering “traditional single-axis horizons” (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 785), which tend to undermine the complexities of the human experience.

From an anti-racist, social justice perspective intersectionality works to show how discrimination and oppression can become a compounded experience due to power dynamics embedded in characteristics such as ethnicity, sex, gender, with the later addition of SES, ability, age, orientation, religion and culture (Crenshaw, 1991; Evans, 2016). For this paper I will focus on Cho, Crenshaw and McCall’s (2013) exploration of the use of intersectionality as a conceptual tool; expanding on their project towards a collaborative field approach. I will therefore help work to imagine ways to develop their main objective which is to:

illustrate its potential for achieving greater theoretical, methodological, [and]

substantive...literacy without demanding greater [homogenization] across the growing

diversity of fields that constitute the study of intersectionality. Implicit in this aspiration

is an understanding of intersectional arenas not as a rigidly delimited set of subfields,

separate from other like-minded approaches, but as part and parcel of them...it would seem

that the future development of intersectionality as a field would be advanced by

maximizing the interface between the centrifugal and the centripetal process. (Cho,

Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 792/794)

Centrifugal processes are defined as those “moving or tending to move away from a center” (dictionary.com) and are referred to as here as those travelling away from its core intention/definition rooted in Black feminism, to other disciplines (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013). These processes seem to apply the standards of their own disciplines and seem to “build…from the ground of empirical research up” (p. 792). Centripetal processes are those “moving or tending to move toward a center” (dictionary.com). These processes are referred to here as those in the margins of their fields who are “skeptical about the possibility of integration mainstream methods and theories into their intersectional research” (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 793). They perhaps try to keep intersectionality free from colonialization, or free from the ’flattening’ of quantitative research that tends to homogenize and stereotype groups.

The colonization of intersectionality refers to when mainstream research, mostly white researchers, use the term and fail to put its use into context, or ignore its originator, Kimberlé Crenshaw (“We’re all Just Different”, 2017). Research using intersectionality should highlight the complications and struggles of Black women’s oppression through policy, law and work (which I will be doing more in my MRP than here). The examination of how white supremacy creates oppression is also overlooked in mainstream research (“We’re all Just Different”, 2017). There are other ways in which the term is colonized, which will be addressed below. Therefore, there are ethical considerations involved in doing research with intersectionality.

Using critical theory as my theoretical framework, I will deconstruct and compare the various ways in which intersectionality is imagined and utilized. Using a multidisciplinary approach (Psychology, Sociology, Gender Studies & Quantum Physics), I will take up the challenge of “synthesizing intersectional projects across disciplines and contexts” (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 793). I will attempt to do this by adding a new practical matrix or heuristic to the theoretical framework.

In order to take up the task suggested by Cho, Crenshaw and McCall (2013), and integrate the various projects, I will have to try and “maximize the interface between centrifugal and centripetal processes” (p. 794). The model/matrix/metaphor/heuristic I will introduce may help in the integration of projects across disciplines because it can be used quantitatively (centrifugal) and qualitatively (centripetal) or both. The purpose of this paper is to look mainly at the various embodied characteristics and flesh out how to conceptualize their compounded nature. Bringing power and oppression back into the picture, I will then use this heuristic to see how power dynamics can be measured in certain situations. The matrix could, in theory, be used to point out certain situations where white supremacy is prominent. After this paper, my MRP will then further work to implement the ideas explored in this paper to policy, law and work, to end up with a more complete picture of intersectional struggles and complexities.

Being a white, middle-class, able-bodied, middle-aged, heterosexual Canadian there are certain ethical considerations required. Using centripetal understandings, I will remember that the term, coined by Crenshaw, a Black woman, was originally used to understand how Black women are discriminated against and how race and gender come together to produce violence and oppression (Crenshaw, 1991). For example, intersectional analysis began as a response to labour and law. Crenshaw (1989) compiled a collection of cases where “Black female claimants were unsuccessful” in their cases due to confusion over intersectionality (p. 790). There was frustration regarding the articulation of the compounded racist and sexist discrimination that left them unemployed (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013). Anti-discrimination laws seem to recognize Black male discrimination and white female discrimination, but do not accommodate for Black-female discrimination (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013). Crenshaw herself should also not be ignored (“We’re all Just Different”, 2017). Therefore, to keep Crenshaw at the centre, I will choose not to use et al. when citing the article of focus, as to keep her name visible throughout the paper. Even though I will venture off into centrifugal conceptions and discuss/incorporate other characteristics that have ‘stretched’ intersectionality out to include SES, ability, age, orientation (Krizsan, Skjeie & Squires, 2012), religion and culture, I will attempt to introduce a mechanism that can have the effect of re-centring the focus of race and sex/gender.

That being said, even though I will discuss all the different characteristics, I will try not to use the appendage etc. The “’et cetera’ problem” (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 787), as I understand it, can lead to the colonization of the term by leaving out certain characteristics that are not focused on in mainstream research circles. By saying etc. researchers can minimize whichever characteristics they wish and push these aspects out to the margins; rendering them invisible.

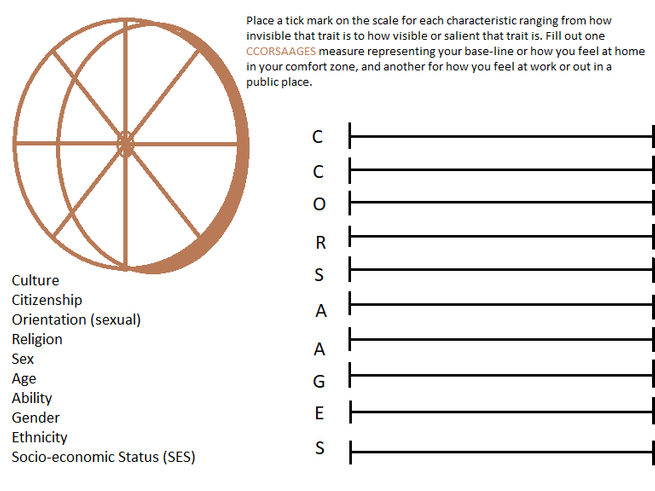

The ‘et cetera problem’ also ignores the fact that these characteristics are compounded and cannot be separated out for analysis. To avoid the ‘et cetera problem’ I have come up with an inclusive acronym that has been chosen, not for its order of appearance, but by the word it spells. This is to stress the importance of the compounded nature of the human experience as well as to show that certain characteristics are not superior to others; nor are certain types of one characteristic better than another. I want to stress the importance of the overall human experience or pattern, rather than the individual pieces/characteristics, so I have chosen the acronym CORSAAGES. My intent is to focus on the flower, its beauty and pattern, rather than its use. However, given that a corsage is something one wears or puts on, it provides an apt analogy. For example, according to Butler (1990/1997), gender is a performance or a “mode of enacting and reenacting” (p. 95), therefore CORSAAGES may be something we put on. I realize some might see the use of the corsage as heteronormative, but I welcome the critique and open it up for discussion. In no particular order, CORSAAGES stands for Culture, Orientation, Religion, Socio-economic Status (SES), Ability, Age, Gender, Ethnicity and Sex. The two characteristics I propose to add to this are time and space, but they are not included in the acronym because these represent the dynamic qualities in which persons are confronted. Time and space are extrinsic influences and not a part of the person themselves.

The ‘et cetera problem’ also addresses the tension between the “fixed versus the dynamic and contextual orientation of intersectional research” (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013, p. 787). My acronym represents the (somewhat) fixed, and the dimensions of time and space represent the dynamic aspects in which a person is placed. The addition of time and space to the equation would allow for the person to be simultaneously (somewhat) fixed, yet also in flux or fluid. This could potentially address the debate regarding

whether there is an essential subject of intersectionality and, if so, whether the subject is

statically situated in terms of identity, geography, or temporality or is dynamically

constituted within institutions and structure that are neither temporally nor spatially

circumscribed. (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013)

I argue that we can be both static and dynamic at once. For example, Sundar (2008) explains that “identity is an expression fitted to the changing demands of the situation” (p.255). She uses the term ‘bi-cultural identity’ to describe the how a person can strategically maneuver their identities to bridge the two worlds of the dominant culture and culture of origin. Therefore, depending on the situation one can get the “best of both worlds” (as cited in Sundar, 2008, p. 255). Therefore, the importance/salience/visibility of each characteristic in CORSAAGES may vary depending on the circumstance (set and setting) rendering some characteristics more or less salient. The matrix/mechanism/heuristic/model I will propose at the end of the paper will attempt to do just this; allow a person to be both simultaneously static and dynamic. First, however, I will engage with some previous research on different methods in which identity is measured, beginning with quantitative matrices, then moving to qualitative heuristics. I will then bring it back full circle to Gender Studies/feminist metaphors of intersectionality.

Centrifugal

Intersectionality came about for many reasons. One reason, as stated earlier, is to challenge single-axis thinking (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013). Single-axis thinking refers to researchers, especially in the social sciences, looking at only one aspect of the human experience. For example, an experiment or study that only looks at sex, or only looks at SES would be examples of single axis thinking. Yet, there are multiple ways in which characteristics come together that create the human experience (Cho, Crenshaw & McCall, 2013) and these characteristics cannot be parsed apart from one another for analysis. As Lorde states “[t]here is no such thing as a single-issue struggle because we do not live single-issue lives” (as cited by “We’re all Just Different”, 2017). The interaction of these characteristics is what produces behaviour; not just one aspect alone. Experiments and studies using only one dimension, therefore produce non-representative and non-generalizable results.

Single-axis thinking also tends to reproduce white, middle-class, patriarchal ideologies by ignoring the full spectrum of human experience. The “issues of masculinity, power, and authority in knowledge creation” are still prominent and feminist critique of methodology used in research is continuously evolving (Doucet, 2006, p. 36). Intersectionality throws a wretch into positivist quantitative methodology because it creates too many dimensions for researchers to examine in one project. For example, quantifying multiple categories for regression analysis reduces power in the experiment to find significant results. Also, quantitative analysis has a tendency towards the mean, levelling out or homogenizing entire populations. All those who do not nicely fit into the average, are considered outliers and are extracted from the analysis altogether. Positivism and quantitative analysis tends to be standardized and white, middle-class, patriarchal interests seem to be the yardstick applied to everyone. This is how intersectionality itself has been appropriated and colonized by western thinkers, by ignoring white supremacy (“We’re all Just Different”, 2017). Even though I understand white supremacy to be wrong, as a white researcher, I need to be careful and respectful when using it as a conceptual tool, especially as I incorporate positivist psychometrics in my mechanism/heuristic. Now that I have discussed examples of single-axis thinking, I will then turn to quantitative methodologies that do try to look at more than one dimension at once; such as psychometrics. The methodology used in psychometrics may be useful for creating models/matrices for intersectionality.

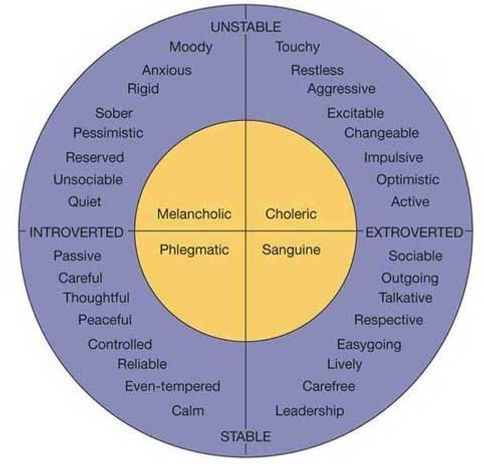

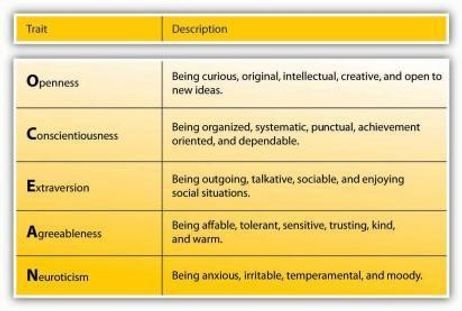

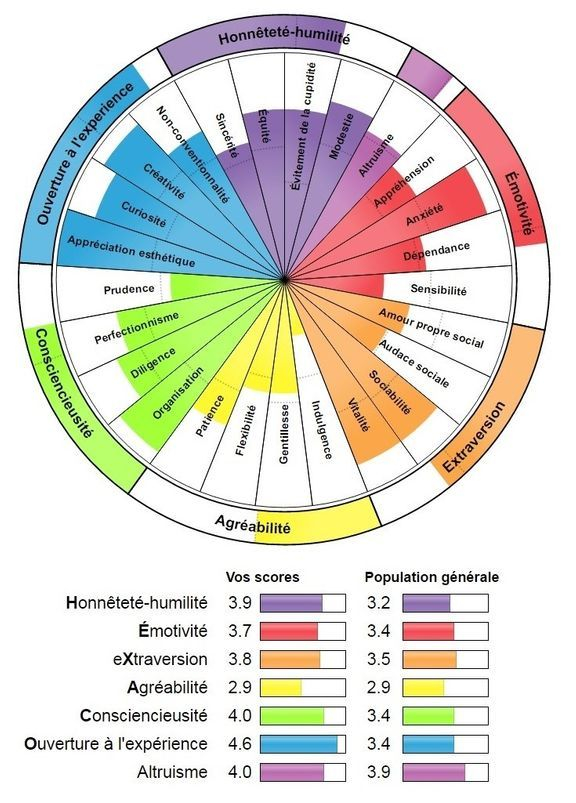

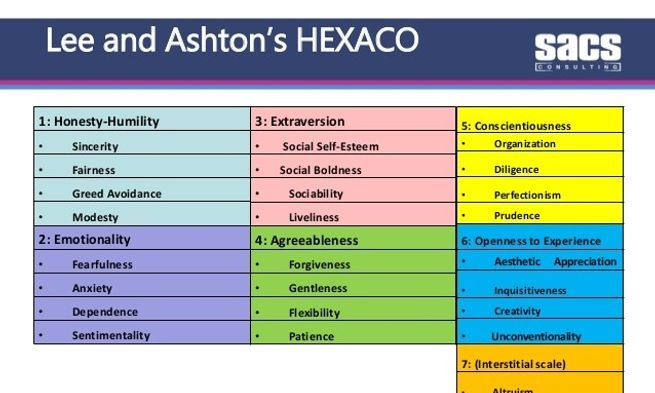

Psychometrics are used in personality assessment and are often influenced by Trait theory. “Trait theories state that personality consists of broad dispositions, called traits, that tend to lead to characteristic responses” (Santrock & Mitterer, 2001, p. 429). I do like how they say, ‘tend to lead to’ but the matrices ‘tend to be’ used to predict and create stereotypes. They attempt to ‘plot’ people onto a matrix that pins them down to certain personality traits. So instead of using traits like CORSAAGES, they measure people on continuums of Introverted vs Extroverted and Stable vs Unstable. Eysenck, who originated personality testing, plotted these on a Cartesian matrix (see Figure 1: Eysenck’s dimensions of personality,1967).

In psychometrics, a questionnaire asks questions related to each dimension and plots people on a continuum for each trait. For example, I tend to score high on Openness to Experience and low on Conscientiousness due to my limited ability to inhibit my behaviour.

Being situated in a continuum, these matrices reinforce and depend upon dichotomous thinking (Hill Collins, 2012). Even though Trait theory models try to use more than one dimension, they keep these dimensions separate in their analysis, then do not report findings based on the aggregated data to put all the pieces back together into an integrated whole person. I like Hill Collins’ (2012) examples of how emotion and reason are not mutually exclusive aspects or the fact that “I don’t stop being a mother when I drop my child off at school, or forget everything I learned while scrubbing the toilet” (p. 61). Therefore, we have many labels or ‘hats’ and they are all with us all the time; some just may be more activated at certain times and spaces.

Seeing the human as a bunch of parts is an example of what are called “pop-bead” analogies or “pop-bead” metaphysics (Spelman, 1988). It seems as though intersectionality itself has been made into a “pop-bead” analogy by adding “beads” of different characteristics onto race, sex and gender. “Pop-bead” or additive analogies or do not seem to work because, even though the beads create one necklace they can still be separated (Garry, 2012). They are also linear, which is limiting to full comprehension of what compounded oppression is like. These analogies can even marginalize and offend those who may feel their particular oppression as “tacked on to the end like an afterthought” (K. Grossman, personal communication, September 2017, regarding disability). Therefore, personality questionnaires seem to divide a person into compartmentalized categories. Even if they could report the aggregated data of all dimensions into one assessment, people are not the sum of their parts (Hill Collins, 2009), which is why, again, “pop-bead” analogies may not work (Garry, 2012). This begs the question of how to incorporate or measure CORSAAGE as a whole, rather than on individual, separate continuums.

Centripetal

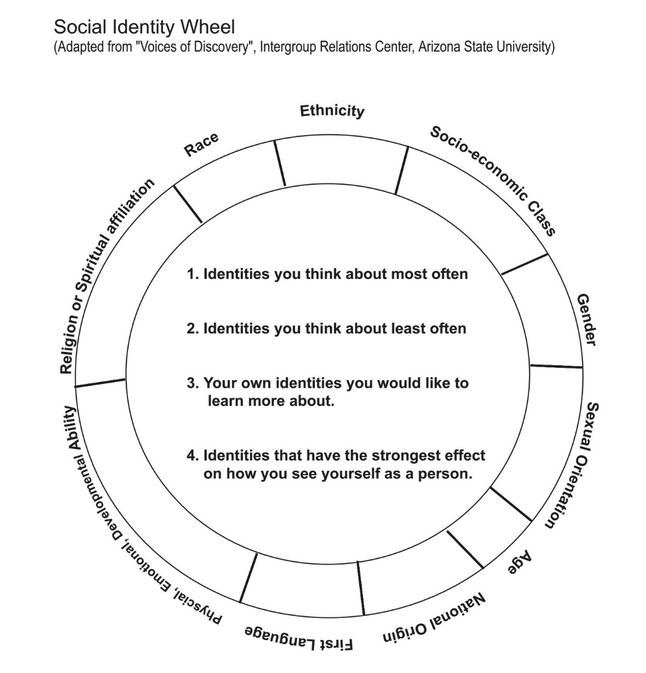

Other models then began to cross disciplinary boundaries, from Psychology into Sociology. One example is the identity wheel (see Figure 4: Other examples of models crossing over disciplines; sociology).